GMRevere

Contents

- 1 PAUL REVERE 1734-1818

- 1.1 TERM

- 1.2 THE REVERE CHARGE

- 1.3 BIOGRAPHY

- 1.3.1 MOORE'S FREEMASON'S MONTHLY, 1859

- 1.3.2 BIOGRAPHY FROM THE 90TH ANNIVERSARY OF WASHINGTON LODGE, 1886

- 1.3.3 1916 PROCEEDINGS

- 1.3.4 NEW ENGLAND CRAFTSMAN, 1924

- 1.3.5 NEW ENGLAND CRAFTSMAN, 1943

- 1.3.6 NEW ENGLAND CRAFTSMAN, 1946

- 1.3.7 BIOGRAPHY FROM 150TH ANNIVERSARY HISTORY OF JERUSALEM LODGE, JUNE 1947

- 1.3.8 MASONIC CAREER OF PAUL REVERE FROM COLUMBIAN LODGE 175TH ANNIVERSARY, JUNE 1970

- 1.3.9 TROWEL, 1984

- 1.3.10 TROWEL, 1984-1985

- 1.3.11 TROWEL, 1988

- 1.3.12 TROWEL, 1996

- 1.3.13 TROWEL, 1999

- 1.3.14 TROWEL, 2009

- 1.4 NOTES

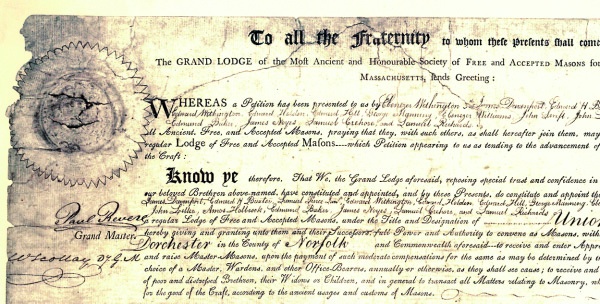

- 1.5 CHARTERS GRANTED

PAUL REVERE 1734-1818

TERM

THE REVERE CHARGE

From New England Craftsman, Vol. XII, No. 5, February 1917, Page 155:

There is preserved in the archives of the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts an old Charge by Paul Revere, delivered by him on several occasions, more than a hundred years ago, when as Grand Master he installed the officers of Masonic Lodges. The Charge referred to is in his own handwriting and is an interesting and suggestive relic. We take pleasure in presenting herewith his words of wholesome counsel as addressed to the Master, Officers and Brethren of a Masonic Lodge:

"Worshipful Master:—

"This W. Lodge, having chosen you for their Master and Representative, it is now incumbent upon you, diligently and upon every proper occasion, to enquire into the knowledge of your fellows, and to find them dayly imployment, that the Art which they profess may not be forgotten or neglected: you must avoid partiality, giving praise where it is due, and imploying those ln the most honorable part of the work who have made the greatest advancement, for the encouragement of the Art. You must preserve union, and judge in all causes amicably and mildly, preferring peace.

"That the Society may prosper, you must preserve the dignity of your office, requiring submission from the perverse and refractory, always acting and being guided by the principles on which your authority is founded. You must, to the extent of your power, pay a constant attendance on your Lodge, that you may see how your work flourishes, and your instructions are obeyed: You must take care that neither your words or actions shall render your authority to be less regarded, but that your prudent and careful behavior may set an example, and give a sanction to your power.

"And as brotherly love is the cement of our Society, so cherish and encourage it that the Brethren may be more willing to obey the dictates of Masons, than you have occasion to command.

"And you, the Officers of this Worshipful Lodge, must carefully assist the Master in the discharge and execution of his office; diffusing light and imparting knowledge to all the fellows under your care, keeping the Brethren in just order and decorum, that nothing may disturb the peaceable serenity or obstruct the glorious effects of Harmony and Concord; and that this may be the better preserved, you must carefully inquire into the character of all candidates to this honorable Society, and recommend none to the Master who in your opinion are unworthy of the privileges and advantages of Masonry, keeping the Cynic far from the Ancient Fraternity, where Harmony is obstructed by the superstitious and morose. You must discharge the Lodge quietly, encouraging the Brethren assembled to work cheerfully, that none when dismissed may go away dissatisfied.

"And you, Brethren of this Worshipful Lodge, learn to follow the advice and instruction of your officers, submitting cheerfully to their amicable decisions, throwing by all resentments and prejudices towards each other; let your chief care be to the advancement of the Society you have the honor to be members of; let there be a modest and friendly emulation among you in do ing good to each other; let complacency and benevolency flourish among you; let your actions be squared by the Rules of Masonry; let friendship be cherished, and all advantages of that title by which we distinguish each other, that we may be Brothers, not only in name, but in the full import, extent and latitude of so glorious an appellation.

"Finally, my Brethren, as this association has been carried on with so much unanimity and concord (in which we greatly rejoice), so may it continue to the latest ages. May your love be reciprocal and harmonious. While these principles are uniformly supported, this Lodge will be an Honor to Masonry, an example to the world, and therefore a blessing to mankind.

"From this happy prospect I rest assured of your steady perseverance, and conclude with wishing you all, my Brethren, joy of your Master, Wardens, and other officers, and of your Constitutional union as Brethren.

"Brother Grand Secretary,— It is my will and pleasure that you register this Lodge in the Grand Lodge Book, in the order of Constitutions, and that you notify the same to the several Lodges."

BIOGRAPHY

We have few Grand Masters whose renown is great beyond the bounds of the Craft, but Paul Revere is a man whose name is known to every schoolchild. We have Henry Wadsworth Longfellow to thank for that -

Listen, my children, and you shall hear / Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-Five;

Hardly a man is now alive / Who remembers that famous day and year.

Revere's part in that famous event has been exaggerated, but he was a hero of the Revolution and a prominent public figure in Massachusetts before, during and after that momentous period. Born in 1734 in Boston to an emigrant Huguenot father and a native Bostonian, he was the second of twelve children, and was apprenticed as a silversmith, in which profession he became well-known. He was initiated in St. Andrew's Lodge in September 1760 at age 25, at which time he was already married and the primary support of his family; as a member of St. Andrew's and later Rising States Lodge, he was an active Blue Lodge Freemason, serving nine terms as Master.

The capstone of his Masonic career was his election as Grand Master in December 1794. His time in office was marked by a rapid expansion of the number of chartered lodges under the jurisdiction of the Grand Lodge. The following lodges received charters while he was Grand Master: Republican (Greenfield), Evening Star (Lenox), Middlesex (Framingham), Cincinnatus (New Marlborough, later Great Barrington), King Hiram's (Truro, later Provincetown), Kennebec (Hallowell, Maine), Fayette (Charlton), Washington (Roxbury), Columbian (Boston), Union (Dorchester), Harmony (Northfield), Thomas (Monson), St. Paul's (Groton), Jerusalem (South Hadley), Adams (Wellfleet), Tuscan (Columbia, Maine), Bristol (Norton), Fellowship (Bridgewater), Corinthian (Concord), Meridian Sun (Brookfield), Olive Branch (Oxford), Montgomery (Franklin), and Meridian (Watertown). Of these twenty-three lodges, nearly all are still in existence (and are justifiably proud of their "Revere Charters"). He also granted new charters to St. Peter's Lodge, Newburyport; Portland Lodge in Portland, Maine; and endorsed the charters of American Union Lodge (then meeting in Marietta in Ohio Territory), Philanthropic Lodge, Marblehead, and Union Lodge in Nantucket. He was also willing to dispense Masonic justice, and under his authority and the vote of the Grand Lodge, Harmonic Lodge of Boston had its charter vacated.

As in the term of Most Wor. Bro. Cutler, Grand Master Revere was responsible for a number of edicts and decisions regarding the functioning of Grand Lodge. Considerable correspondence with other Grand Lodges near and far took place, as well as other exchanges of letters, most notably with Brother (and former President) George Washington. He was also active in the public sphere, notably in the laying of corner stones for public buildings, including the Massachusetts State House in 1795. (When Most Wor. Winslow Lewis was invited to perform the same ceremony in September 1855, he was surprised to find the remains of that stone and the memorabilia placed therein.) Paul Revere was a remarkable man, and a memorable Mason.

MOORE'S FREEMASON'S MONTHLY, 1859

From Moore's Freemason's Monthly, Vol. XVIII, No. 12, October 1859, History of St. Andrew's Chapter; Page 363:

Col. PAUL REVERE was descended from the French Huguenots, and was born in Boston, on the 1st of January, 1735. He was brought up to the business of a goldsmith, and became a very expert workman. In 1756, soon alter he became of age, he joined an expedition that was organized against Crown Point, then in possession of the French, receiving the appointment of lieutenant of artillery, and was stationed at Fort Edward, on Lake George, during the greater part of that year. After returning to Boston he married and settled in business as a goldsmith. He also carried on engraving and some other mechanical arts, during a long and active life. He was a bold and fearless advocate for American Independence, and one of the persons who planned and executed the most daring feat of the times, the destruction of the tea in Boston harbor. He was often entrusted with confidential messages from the Provincial to the Continental Congress, and acted an important part in the events which occurred about the 19th of April, 1775. A regiment having been raised in Boston and the vicinity, for the defence of the State, Revere was appointed a Major and afterwards Lieutenant Colonel, and remained in the service until the close o f the war. In 1768 he took an active part in favor of the Constitution of the United States, and, with other leading macbanics, exerted his influence to promote its adoption. Col. Revere died in Boston, in May, 1818, aged eighty four years. At the time of his decease, (to adopt the language of another,) he was connected with many of the benevolent and useful institutions which dignify and embellish the metropolis of Massachusetts, in all of which he was an active and munificent member. By an uncommonly long life of industry and economy he was able to obtain a competency in regard to property, and to educate a large family of children, many of whom are living [1S54] to enjoy the contemplation of the character of an upright, patriotic, and virtuous father.

Brother Revere's name appears on the records of our Chapter, for the first time, January 9th, 1770. There is no doubt he was a member at this early period, for he was Junior Warden of the "Royal Arch Lodge," in the year 1770. Probably this ceremony was practised in the admission of members, eighty years ago, than at the present time; and no register of names extending back so far as the above date, can now be found. He was Senior Grand Warden of the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts, in 17S2, and Grand Master in 1795, 1796, and 1797.

BIOGRAPHY FROM THE 90TH ANNIVERSARY OF WASHINGTON LODGE, 1886

1916 PROCEEDINGS

Most Worshipful Brother Paul Revere was an active and zealous Mason. He was initiated in St. Andrew's Lodge, September 4, 1760, and raised January 27, 1761; was elected Senior Warden in November, 1764, and Master, November 30, 1770. In the Massachusetts Grand Lodge, in 1777, 1778, and 1779, he was Junior Grand Warden; in 1780, 1781, 1782, and 1783, Senior Grand Warden; and in 1784, 1790, and 1791, he was Deputy Grand Master. He was the second Grand Master after the union and served in that office from December 12, 1794 to December 27, 1797. An interesting and ably written short biography of Brother Revere may be found in Volume III of the New England, Magazine, edited by Brother Joseph T. Buckingham. An abridgment of that biography presents the following facts:

"Paul Revere, or Rivoire, as his ancestors wrote the name, was born in Boston, in December, 1734, O. S. (January 1, 1735), and died there in May, 1818, aged 84. His grandfather emigrated from St. Foy, in France, to the Island of Guernsey; and his father, at the age of thirteen, was sent by his friends from that island to Boston, to learn the trade of a goldsmith, where he afterwards married, and had several children, of whom Paul was the eldest. Young Revere was brought up by his father to the business of a goldsmith and made himself very serviceable in the use of a graver. Having a natural taste for drawing he made it his peculiar business to design and execute all engravings on the various kinds of silver plate then manufactured. In 1756, he received the appointment of Lieutenant of Artillery and was stationed at Fort Edward, on Lake George, the greater part of that year. After his return to Boston he married and commenced business as a goldsmith which, with engraving and other mechanical and manufacturing arts, were objects of industry from time to time during a long and. active life. He was one of a club of young men, chiefly mechanics, who associated for the purpose of watching the movements of the British troops in Boston and acted an important part in the events which occurred. about the 19th of April, 1775. He says, in a letter he wrote to the Corresponding Secretary of the Massachusetts Historical Society, We held our meetings at the Green Dragon tavern. We were so careful that our meetings should be kept secret; that every time we met, every person swore upon the Bible, that they would not discover any of our transactions, but to Messrs. Hancock, Adams, Doctors Warren, Church, and one or two more."

After the British evacuatecl Boston a regiment of artillery was raised for the defense of the State. In this regiment he was appointed a Major, and afterwards a Lieutenant Colonel, and remained in the service until the peace. When the British left Boston they broke the trunnions of the cannon at Castle William (Fort Independence) and Washington called on Revere to render them useful - in which he succeeded by means of a newly contrived carriage. After the peace he resumed his business as a goldsmith. Subsequently he erected an air-furnace in which he cast church bells and brass cannon. The manufacture of copper sheathing also engaged his attention and he was successful in this undertaking. Colonel Revere was the first President of the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanics Association, instituted in 1795. At the time of his death he was connected with many other philanthropic associations, in all of which he was a munificent and useful member.

The life of Col. Paul Revere by E.H. Goss (1891).

Centennial Memorial of the Lodge of St. Andrew (1870).

Heard's History of Columbian Lodge, Pages 351-353 'i:

15 M.F.M. 169.

1909 Mass. 25.

NEW ENGLAND CRAFTSMAN, 1924

From New England Craftsman, Vol. XIX, No. 7, April 1924, Page 206:

Note that there are some inaccuracies in this account.

Paul Revere, Patriot, engraver, gold and silversmith, was born in Boston on January 1st, 1735. He early took an interest in public affairs, and became active in Freemasonry. There was organized in Boston in 1752 in the Green Dragon Tavern on Union St. a Masonic lodge which was named St. Andrew's lodge, afterwards called the Lodge St. Andrew.

This lodge met continuously at the Green Dragon Tavern but did not receive its charter from the Grand Lodge of Scotland until 1760. Paul Revere was a member of this lodge.

At the same time there was and had been since 1733 lodges in Boston, chartered by the Grand Lodge of England, with a Provincial Grand Master of New England. Between these lodges was a good deal of rivalry and as a general rule neither they nor their members affiliated with each other. The reasons are not difficult to understand. The greater part of the membership of the lodges chartered by the Grand Lodge of England were loyal to the King during the agitation leading up to the Revolutionary War. The members of St. Andrew's Lodge, most without exception including Dr. Joseph Warren, afterward General Warren, and Paul Revere organized the "Sons of Liberty" in the lodge room at the Green Dragon Tavern.

Paul Revere had a leading part in bringing together the patriots who gathered on November 29th, 1773 first at Faneuil Hall, at the Old South Meeting-House to protest against landing the tea from the ship Dartmouth. The celebrated "Boston Tea Party" was held December 16th, 1773, at a regular meeting night of St. Andrew's Lodge, the lodge secretary records that the lodge was not open for business on that night because of absence of so many members on tea business. The Grand Master of the English Grand Lodge had a ship load of tea in the harbor and it went overboard with the rest and he subsequently expressed the wish that had never had anything to do with the business.

In preparation for the rallying of the men the tea party at the Green Dragon Tavern following ditty was composed:

My Mohawks!! bring out your axes,

And tell King George we'll pay no taxes

On his foreign tea,

His threats are vain, and vain to think

To force our girls and wives to drink

His vile Bohea.

Then raiiy boys and hasten on

To meet our Chief at the Green Dragon.

Old Warren's there, and bold Revere

With hands to do and words to cheer

Eor liberty and laws.

Our Country's brave and free defenders

Shall ne'er be left by true North Enders,

Fighting Freedom's cause.

Then rally boys and hasten on

To meet our chief at the Green Dragon.

Paul Revere was Grand Master of Masons in 1795, laid the cornerstone of the Massachusetts state capitol building and Samuel Adams delivered the oration. In that same year Paul Revere founded the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association and was its first president.

In addition to being a Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Masons, he was Junior Warden, or as now called Scribe, of St. Andrews Boyal Arch Chapter, at the time Thomas Alexander was Royal Arch Master, or as now called Excellent High Priest. There appears to be no record of his having been advanced to the head of the Chapter.

He was one of the thirty North End mechanics who patrolled the streets to watch the movements of the British troops and Tories.

He was commissioned a Major of Infantry in the Massachusetts militia in April 1776 and was promoted to the rank of Lieut. Colonel of Artillery in November and was stationed at Castle William defending Boston Harbor, and finally received command of that fort.

After the war he engaged in the manufacture of gold and silverware and his productions may be found in many of the best collections in the country. He was first married in 1757 and had eight children, and after the death of his wife he married Rachael Walker in 1773. He lived for many years in the house that now bears his name, in North Square, Boston, not far from Christ's church. This house has been restore to its ancient form and is now a museum of Revolutionary Relics and is visited by thou sands of tourists annually.

He died in Boston, May 10th, 1818 and was buried in the Old Granary Burying-Ground on Tremont St., near Park Street.

NEW ENGLAND CRAFTSMAN, 1943

From New England Craftsman, Vol. XXXVIII, No. 8, April 1943, Page 177:

PAUL REVERE, ROYAL ARCH MASON

By Melvin M. Johnson

(Dr. Melvin M. Johnson has contributed this article on ip of Massachusetts' most outstanding Freemasons. It me to the editor marked "Notes on Paul Revere" but i have changed its title to bring out Revere's Royal Arch membership. The writer is one of America's distinguished and versatile Craftsmen, Past Grand Master of Massachusetts Grand Lodge and for many years the Sovereign Grand Commander of the Northern Jurisdiction of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry.) - Ed. Note.

Col. Paul Revere, or Rivoire, as his ancestors wrote the name, was born in Boston, in December 1734, O. S. (January 1, 1735). and died there in May, 1818, aged eighty-four. His grandfather emigrated from St. Foy in France, to the Island of Guernsey; and his father at the age of thirteen was sent by his friends from that island to Boston, to learn the trade of a goldsmith; here he afterwards married and had several children, of whom Paul was the eldest. Young Revere was brought up by his father to the business of a goldsmith and made himself very serviceable in the use of a graver. Having a natural taste for drawing he made it his peculiar business to design and execute all engravings on the various kinds of silver plate then manufactured.

His business interests were very extensive. He was primarily a gold and silversmith, designing and furnishing many articles, many of which are preserved today and are almost priceless. He was the best engraver of his day. One sample of his work is the plate for printing the first Continental scrip money in 1778. He manufactured gun powder, cast church bells and cannon and maintained an iron foundry and hardware store. He established the first rolling mill for copper sheathing, in which he made plates for Robert Fulton's steamboats. He was probably the first manufacturer of artificial teeth in the Western Hemisphere.

In Freemasonry, he was active and zealous. Initiated in St. Andrew's Lodge September 4, 1760, and raised January 27, 1761, he was elected Senior Warden in November 1764 and Worshipful Master in November 1770. Later, there was a schism in the lodge and Revere was one of the dimitting members, immediately becoming active and almost dominant in Rising States Lodge. In the Massachusetts Grand Lodge (this being the one which descended from Scotland, and not the one founded by Henry Price), he was Junior Grand Warden, 1777-79 inclusive; Senior Grand Warden, 1780-83 inclusive; and Deputy Grand Master in 1784, 1790 and 1791. After the union of the two Grand Lodges in Massachusetts, which occurred in 1792, Revere became the second Grand Master and served in that office from December 12, 1794 to December 27, 1797.

The records of the Royal Arch Lodge held in Boston record the fact that —

"The petition of Brother Paul Revere coming before the Lodge begging to become a Royal Arch Mason, it was rec'd & he was unanimously accepted & accordingly made."

The official date of his admission to the Chapter was December 11, 1769; he became Junior Warden during the year 1770, "in which position he aided to confer the degrees on General Joseph Warren of immortal memory, on May 14th, following his own admission." (From the records of St. Andrews' Royal Arch Chapter.)

Revere was known as the Mercury of the American Revolution. He was one of the most active of the leading patriots of the pre-Revolutionary Period, being a member of a committee charged with the duty of collecting the names of all persons who in any way acted against the rights and liberties of America. In this he was associated with Hancock, Adams, Warren, Pulling, among others.

He was also a member of a club of young men, chiefly mechanics, who associated for the purpose of watching the movements of the British troops in Boston. Both the committee and the club were accustomed to meet at the Green Dragon Tavern, owned by the Lodge of St. Andrew, the property still belonging to this lodge.

In one of his letters, he wrote:

"We were so careful that our meetings should be kept secret that every time we met, every person swore upon the Bible that they would not discover any of our transactions, but to Messrs. Hancock, Adams, Doctors Warren, Church, and one or two more."

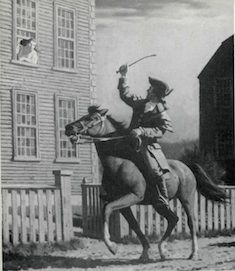

Longfellow immortalized Revere's ride, but, in part, the poet was in error. It may be worth while to tell the story correctly. The 18th of April, 1775, was Tuesday; and Paul, himself, tells the story of that day and the next—in part—as follows:

"On Tuesday evening it was observed that a number of soldiers were marching toward Boston Common. About ten o'clock, Dr. Warren sent in great haste for me and begged that I would immediately set off for Lexington, where were Hancock and Adams, and acquaint them of the movement, and that it was thought they were the objects.

"On the Sunday before I agreed with Col. Conant and some other gentlemen — in Charlestown — that if the British went out by water we should show two lanterns in the North Church steeple, and if by land one as a signal, for we were apprehensive it would be difficult to cross over Charles River.

"I left Dr. Warren, called upon a friend and desired him to make the signal. I then went home, took my boots and surtout, went to the north part of the town, where I had kept a boat. Two friends rowed me across the Charles River, a little to the eastward where the Somerset lay. It was then young flood; the ship was winding and the moon was rising. They landed me on the Charles town side. When I got into town I met Col. Conant and several others. They said they had seen our signals."

It has generally heen reported on the authority of Rev. Dr. Burroughs that the friend referred to in the above quotation was Robert Newman, who was the sexton of the old North Church. He was wrong. On the morning after the ride, the sexton was arrested. He protested his innocence, asserting that at a late hour, the night before, the keys of the Church were demanded of him by John Pulling who, being a vestryman, was entitled to them. After Newman had given the keys to Pulling he went to bed, and had nothing to do with the hanging of the lanterns. This was done in fact hy Pulling, who was not only a close friend of Revere hut also a brother Mason, having originally been made in Marblehead, affiliating with the Lodge of St. Andrew in 1761. Pulling was a dealer in furs which he purchased principally in Canada and Newfoundland, but imported some merchandise from Europe. He was also a patriot and a most fearless and devoted asserter and defender of liberty. Again, and again, Pulling and Revere are mentioned together as officers in the Continental service and members of the Committee on Safety. He was on the committee to which reference has already been made, and undoubtedly was a member of the Boston Tea Party, engineered by Revere on December 16, 1773.

When the British learned that Pulling was the man who had obtained the keys of the Church from the sexton they searched his house at the corner of Ann and Cross Streets in Boston. They were not very thorough, for they failed to find him where he was concealed by his mother under an empty wine butt in the cellar. Shortly thereafter he escaped in a small skiff by disguising himself as a fisherman. Landing on Nantasket Beach, he was joined by his wife. They remained in concealment for awhile in an old cooper shop near the beach. All his property, real and personal, was confiscated, his house being occupied by British officers. After he was able to return to Boston, he never succeeded in re-establishing himself financially on account of this seizure, and he died in comparative poverty in 1787.

Revere's ride on 18th April 1775, was not his only one for he was frequently employed as a messenger between Boston, New York and Philadelphia, making the trip on horseback. Contrary to the generally accepted theory as told by Longfellow, Revere never reached Concord. He had proceeded from Charlestown as far as Medford where he was captured by British officers. He escaped and reached Woburn. He and others had attempted to get to Concord. Another rider, Dawes, was also captured and did not reach Concord, but Col. Prescott escaped and did reach Concord, accomplishing the mission on the way of warning Hancock and Adams who were in hiding in Lexington and who were conducted from there by an ancestor of the author to a safer place of hiding in Burlington, where they remained until after the British had returned. After the British evacuated Boston, a regiment of artillery was raised, of which Paul Revere was made Major. Among other things, he restored the cannon to usefulness which the British had put out of commission. Later, in 1776, he was made Lieutenant-Colonel and remained in service throughout the war.

Revere was a strong advocate of the adoption of the Constitution of the United States and remained active in civic affairs until his death.

While Grand Master, he laid the cornerstone of the State House in Boston, with Masonic ceremonies: and the articles placed therein came to light when repairs were made in 1855. They were replaced with others in the cornerstone at that time by Grand Master Lewis. Note: the printed article says "Webb", but this is in error.

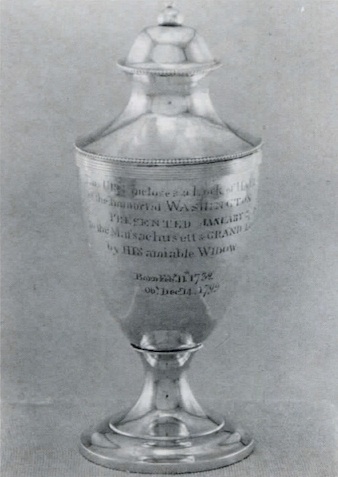

The Grand Lodge of Masons in Massachusetts possesses as one of its greatest treasures a lock of the hair of George Washington, which is kept in a golden urn made by Revere's own hand. Revere was one of the committee who obtained this lock of hair from Washington's widow, since which time it has been physically transmitted by each Grand Master, when retiring from office, to his successor.

NEW ENGLAND CRAFTSMAN, 1946

From New England Craftsman, Vol. XLI, No. 9, September 1946, Page 238:

PAUL REVERE, GRAND MASTER

SILVERSMITH — COPPER ROLLER — ENGRAVER

Long ago we should have revised our view and enlarged our picture of Paul Revere, who was horn in Boston, January 1, 1735. and definitely deserves to he rememhered as something hesides a patriotic horseman. The fact of the matter is that Revere was an important businessman of his day. Also he was a manufacturer of distinction.

Moreover, the "ride" that made him famous was merely an incident in his service to his country.

In the spring of 1776 we find Revere successfully supervising the manufacture of gunpowder, every keg of which helped to make American history. From the making of gunpowder he turned to easting cannon for our military forces. In 1792, after the revolution, he hegan to manufacture hells, the first of which, historians say, was erected in the church in which he worshiped.

He was an etcher and engraver on copper of hook plates, dies, seals, including views of scenic interest in and about Boston. In silver and gold he created exquisite things still treasured by the Boston Museum of fine arts and the Metropolitan Museum.

Other glimpses of him at different periods of his life suggest how active a man of affairs lie was. He was appointed coroner of Boston in 1796. His name headed the list of charter members of the first effort in America to insure property against fire, that of the Massachusetts Fire Insurace Company, chartered in 1798. He served on a patriotic committee to "collect all names of enemies of this Continent" and was the first chairman of the Boston Board of Health. The cause of liberty received the full benefit of his versatility. He was an ardent member of the Sons of Liberty. He engraved and printed on a press of his own manufacture the first paper money issued by our government. He was one of the earliest cartoonists an his work in this line did much to build up sentiment in the Colonies against Great Britain.

All these things, however, were among his minor achievements. It was not until 1800 when he was well past 60 that Paul Revere made his greatest contribution to American industry — the mastery, technically as well as commercially, of the secrets of rolling copper.

Revere was prompted to make the experiments that resulted in his discovery by the spirited rivalry in shipping between British and American sailng vessels. Copper came onlv from England, and onlv copper could keep ther bottoms clean and free from borers. If America was to keep in the race America had to produce her own copper because ability to get it from England decreased as rivalry on the sea increased.

How well Revere succeeded in learning the secret of rolling copper that was held only by England, is revealed by the fact that in 1803 The Constitution, "Old Ironsides," was sheathed in copper of his manufacture. Incidentally we learn from Revere's correspondence thai he furnished copper sheet to the government for two years without having received a shilling in pay. However, he did not write the Secretary of the Navy for money until his bill had reached nearly $15,000.

And so let us give just a little of our admiration to the man whom histories have practically ignored and whom the kindly poet Longfellow has made us picture as only an accomplished horseman.

That Paul Revere was a Mason is a fact familiar to most Masons. He was initiated in 1761 in historic St. Andrew's Lodge, Boston, served as Master in 1770, and was exalted to the sublime degree of a Royal Arch Mason the same year. He was Senior Grand Warden of the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts and served as Grand Master during the years 1795, 1796 and 1797. How closely his life was entwined about the Craft, many are not so well informed upon.

Relatively there must have been as great a proportion of Masons in the British army as there was in the American forces, and yet Lafayette is stated to have said that Washington had told him "that he hesitated to place command in one not of the mystic tie." This may have influenced the statement frequently made that all the signers of the Declaration of Independence and all of Washington's generals were Masons, which is, unfortunately, not entirely true.

The "Ancient" Lodge in Boston met at the Green Dragon Tavern, which became known as "Freemason's Arms." and termed by the Royalists "A nest of sedition." and was referred to by Daniel Webster as "the headquarters of the Revolution." Here met the "Sons of Liberty," Paul Revere's famous club, and other revolutionary bodies.

The first bloodshed in the conflict was on March 5, 1770. which was portrayed for posterity by Bro. Paul Revere in his well-known engraving, termed "The Boston Massacre."

No sooner was the "Boston Tea Party" completed than Bro. Revere was off with the news to New York and Philadelphia, and was so anxious to return to the scene of action that he completed the journey on horseback in eleven days. His celebrated ride by night to warn the patriots of the intent of the British to destroy the military supplies at Concord is one of the dramatic incidents of history and was immortalized hv Longfellow.

It was in the Masonic lodge that Paul Revere saw the actual working out of our great American dcmocracy. The Massachusetts social system, like the British, elevated men of title to high office and thus an exclusive circle justified its right to govern the ordinary man by claiming that they were superior. It was only in the Masonic lodge that the ruling class and the ordinary man ever met personally and it was from these lodge associations that the various classes found that they were indeed born with equal ability, mentality and character, which long had heen the contention of Revere.

Among the choice relics in possession of the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts is an urn of gold fashioned by Bro. Revere, which contains a lock of the hair of Bro. George Washington.

BIOGRAPHY FROM 150TH ANNIVERSARY HISTORY OF JERUSALEM LODGE, JUNE 1947

MASONIC CAREER OF PAUL REVERE FROM COLUMBIAN LODGE 175TH ANNIVERSARY, JUNE 1970

TROWEL, 1984

From TROWEL, April 1984, Page 2:

REVERE THE MASON

Paul Revere was made a Mason in the Lodge of Saint Andrew of Boston, September 4, 1760. That Lodge, chartered by the Grand Lodge of Scotland in 1756, was made up of Masons meeting in the Green Dragon Tavern and working without authority, and British Regiments quartered in Boston, some belonging to the Grand Lodge of Scotland and others to the Grand Lodge of Ireland.

He held several offices in the Lodge of St. Andrew, serving as Master in 1770-71, 1777-79 and 1780-82. When the Massachusetts Grand Lodge was also chartered by the Grand Lodge of Scotland in 1769, with Joseph Warren as its Grand Master, the Lodge of St. Andrew was a part of it. Revere was Junior Grand Warden 1777-79, Senior Grand Warden 1780-83 and Deputy Grand Master 1784-85 and 1791-92.

When the union of the Massachusetts Grand Lodge and the Saint John's Grand Lodge formed the Grand Lodge of Masons in Massachusetts in 1792, Revere was the second Grand Master. During his term, 1795-97, twenty-three Lodges were chartered. Only a few have become extinct.

On September 2, 1784, by vote of the Massachusetts Grand Lodge, a Lodge named St. Andrew's had its name changed to Rising States. (I Mass. 320; O.R. St. Andrews-Rising States Lodge, July 26 and August 30, 1784.) The new and confusing St. Andrew's Lodge resulted from a schism in the old Lodge of St. Andrew on November 30, 1756.

In the period preceding the union in 1792 there were two opposing groups in the Lodge of St. Andrew, one of which did not wish to join in the union. Those opposing formed Rising States Lodge under a Massachusetts charter. Among the more prominent men of St. Andrew's who joined in the movement was Paul Revere. In 1803 the report of a trial in Rising States brings out the fact some of its officers were found guilty of un-Masonic conduct, in that they used the charter, regalia and jewels of the Lodge in conferring some of the so-called "higher degrees" and were punished by reprimand and expulsion. In 1810 dissatisfaction arose among the members because the Lodge of St. Andrew, in spite of the agreement made at the time of the union, had precedence over Rising States.

In December, 1810, a committee from the Lodge appeared at Grand Lodge to surrender its charter. A committee appointed by the Grand Master learned the money of Rising States Lodge had been divided among twenty-five men when only nineteen members had been shown on the roll. The result of the investigation showed most of the members could prove they had expended their money for charitable purposes. Only one was expelled.

Paul Revere died May 10, 1818, at age eighty-three. From the time he received his First Degree in St. Andrew's Lodge, after its charter had been received from the Grand Lodge of Scotland in 1760, until the last record of his presence in Grand Lodge in 1804, he had been a creative force in Massachusetts Masonry. Yet, there is no record of his death in the Grand Lodge Proceedings and no Masonic honor paid to him at his funeral.

The Boston Centinel, owned and edited by Benjamin Russell (past Grand Master of Masons in Massachusetts and Grand Marshal when Revere was Grand Master), printed only a two-inch story of Revere's death with no reference to his Masonic honors. It must be assumed that Benjamin Russell's rebuke toward Revere and the Rising States controversy influenced the brief news coverage. It also proved Russell was biased and not an honest reporter.

It is estimated that Paul Revere and his son, Joseph Warren Revere, cast 400 bells from 1792 to 1826. The largest, weighing over 2,000 pounds, was cast in 1816 and today it still hangs in the tower of King's Chapel (1686), Tremont Street, Boston. The magnificent bell tolled 83 times the day Revere died. He was interned in Old Granary burial ground, not far from King's Chapel, where can be found the final resting places of James Otis, John Hancock, Robert Treat Paine, Samuel Adams and others.

REVERE THE REBEL

Written by Robert W. Williams III

Most American heroes of the Revolutionary War era are by now two men; the actual man and the romantic image. Some are three; the actual man, the image, and the debunked remains. Paul Revere, it has been written, has not suffered so much from the debunkers. Although there have been rumors he never made his famous ride, we do know he was an engraver. His work of the Boston Massacre in 1770 is proof of his craftsmanship. The worst that can be said of him is that he was a middle-aged goldsmith on a stout plough horse. His reputation can be separated into pre- and post-Longfellow periods.

At 11 P. M., 209 years ago, on the 18th of April, Paul Revere leaped on a spirited horse loaned to him by his friend Deacon John Larkin. Leaving Charlestown he started on one of the most colorful adventures in American History'- Every American should know that this Boston hero warned the countryside that the British were on a march that would precipitate skirmishes at Lexington and Concord where the "shot heard 'round the world" would begin the first of many battles of the revolution.

The son of a French Huguenot who had Americanized his name from Apollos Rivoire to Revere, and of Deborah Hitchbourn, Paul was baptized January 1, 1735. The exact date of his birth is not known. He married Sara Orne in 1757. They had one son, Paul, and seven daughters. Only Mary survived her father's death in 1818. Sara died in May of 1773 and in September he married Rachel Walker to help him care for his large family. Their union produced eight more children, four of whom died before their father. Rachel died in 1813.

Who was this man made famous by historians and best brought to the forefront by the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow? He was a man who belonged to the North Caucus, a group set up to control the government by keeping it in the hands of the Whigs and out of the hands of the Tories. He met with a society of Harvard graduates in the Long Room Club and he was the lone artisan of the group. He was a man worth watching ... a man capable of bridging the very real gap between the thinkers and the doers.

Aware he had been tagged a rowdy rebel by the British, he was aged 40 when he made his famous ride. He was a spirited citizen who left the warmth of his home where his wife, children, and mother lived in North Square. Did he believe in what he was doing? Was he a pawn for others more politically motivated? Was Revere too obtuse to be aware of fear?

He knew the dangers that could confront him, but he risked his life, his family, and the lives of those associated with him. He knew that if his ride to alarm others was successful it would open the way to freedom and liberty in the new world and unshackle the chain the British held around the Colonies.

How could the poet Longfellow do justice to Revere's famous ride? Revere was 73 years of age when Longfellow was born in Portland, Maine. The poet didn't settle in Cambridge until 1836, 18 years after the death of Paul Revere. How could he know about Revere?

The earliest biographical sketch of Revere is found in the New England Magazine (1832). The author seems to have known him personally. He is mentioned as a 'messenger.' There are other stories written of him. In 1855 May Street was renamed Revere in his honor. Some historical reviews fail to mention Revere, but others tell about him. In 1835 Dr. Joseph Warren's sister wrote a child's life of General and Doctor Warren who was killed at the Battle of Bunker Hill. (Actually it was Breed's Hill.) It is a dialogue between a mother and her children; in it "Col. Revere" is mentioned along with the famous ride and his escape "from the British officers on Charlestown Neck."

Paul Revere's ride had assumed legendary form when Longfellow made him more famous. But had the poet followed Revere's own account, it is unlikely he would have made the mistake of placing Revere on the wrong side of the Charles River and bringing him all the way to Concord. What about John Pulling, the Vestryman of Christ Church, now known as Old North Church?

In 1895 M. W. Edwin B. Holmes, Grand Master of our Grand Lodge (1895-96), reported he had made a careful study of the available evidence and concluded it was Brother Pulling who hung the lanterns, not Robert Newman, the church sexton. Newman, later a Mason, climbed from his bedroom window, slid down the roof, and hastened to the church, where Pulling admitted him in secrecy. Newman's mother was hosting some British officers at tea that evening, prohibiting her son any safe exit by door.

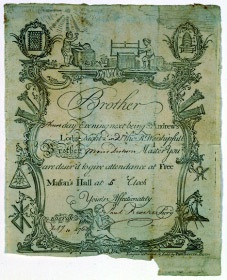

Newman had secured the keys to the church the night before the event, apparently handing them to John Pulling, who arrived at the church first. But Newman is credited with climbing the belfry stairs to hang the "two-if-by-sea" lanterns to warn Paul Revere. Brother Pulling, made a Mason in the Lodge at Marblehead (now Philanthropic Lodge, 1760), took a risk in whatever role he played. Our Grand Lodge is the prized possessor of the Master Mason diploma issued to John Pulling, Jr., in June, 1761.

While Robert Newman had been taken into custody by the British when it was learned he had secured the keys, Pulling escaped. He disguised himself as a fisherman and took a small skiff to Nantasket, leaving his business and all he possessed behind. He was a shipping merchant and his vessels and goods were confiscated by the British. After the siege of Boston he returned and continued to devote himself to the cause of liberty. Pulling never fully recovered from his financial losses suffered in the cause. In leaving his North Square home to face his rendezvous with history, Revere, in great haste, forgot his spurs and two pieces of cloth to muffle the oars during the crossing of the Charles River. Two trusted non-Masonic friends had hidden a boat on the river bank. Joshua Bently, a boat builder, and Thomas Richardson were waiting to row Revere across. To row clear of the Frigate Somerset, the men had to take the boat almost to the open sea. Deacon Larkin's horse was waiting and Revere began a ride which, in a way, has never ended.

Although Masonry as an organized institution took no part in the dramatic events of that day, nevertheless the fundamental teachings and precepts of our institution were actively at work, manifested through the heroic deeds of those members of the Craft who were playing leading roles in the blood-curdling drama being staged.

On the 16th of December, 1773, a band of colonists disguised as Indians climbed aboard three British merchant ships anchored at Griffin's Wharf, Boston. In a protest against the tax on tea, the entire cargo of tea from the ships was dumped into the water. Two of Revere's organizations, the North Caucus and the Lodge of St. Andrew, are known to have played a major role in the event. The British Parliament retaliated by enacting the Intolerable Acts of 1774.

Revere's Masonic Lodge owned the Green Dragon Inn. The large brick building stood on Union Street where, hanging from an iron branch hammered out of copper, was the dragon already green with verdigris and time. More Revolutionary eggs were hatched in that dragon's nest than in any other spot in Boston. Plans to destroy the tea were made there but the Indian disguises were donned in the home of Benjamin Edes or in that of Revere (probably both).

The members of the Lodge of St. Andrew met the night before the ships arrived, but the minutes of that meeting read: "Lodge adjourned on account of a few members present. N. B. Consignees of Tea took the Brethren's Time." The meeting of December 16, 1773, states: "Lodge closed on account of few members present." Beneath those words has been drawn a large T. Through the kindness of R. W. William C. Loring, Deputy Grand Master in 1982 and a proud member of the Lodge of St. Andrew, I have seen and read those minutes of the meetings. The Lodge still owns tall candleholders and a punch bowl made by Paul Revere, who became a member of the Lodge in 1760.

Revere made four famous rides to Philadelphia, one of which was to alert the Continental Congress about the Suffolk Resolves. In December of 1774 he rode to Durham, New Hampshire, to notify the Sons of Liberty that the British were planning to send reinforcements to Fort William and Mary in Portsmouth Harbor to prohibit the local militia from seizing the stores of munitions.

Masonry as an organized institution cannot officially endorse all of the worthwhile non-Masonic activities, regardless of their inherent value or importance. But as individual Masons we should be constantly aware of the obligations and duty the Craft teaches us to become identified and to be participants in activities within our own communities.

Because of the great interest which we have as Masons in the historic institutions of America, the Grand Lodge of Masons in Massachusetts contributed five hundred dollars to go with the one hundred dollars given by the Masonic Service Association toward the cost of reconstructing the belfry of Old North Church that had been damaged in 1954 in Hurricane Carol. When the bells were taken from the belfry in 1981 our Grand Lodge contributed one thousand dollars toward the repairing of the belfry and bells. On September 3, 1983, the bells peeled again to remind the world of the 200th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Paris that brought an end to the American Revolution. Saint John's Lodge of Boston, the oldest Lodge in America, opened, its members attended the festivities at Old North, and the Lodge closed on both occasions.

It is not beyond reason to assume that if Masons had not been inspired and sustained by the precepts of our beloved institution they might never have been willing to risk their lives and property for the establishment of the principle of "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" in a free land. When viewed in this way, it is obvious that the contribution Masonry makes to any cause can never be adequately measured, but it is equally obvious that the teachings of the Craft, when injected into the mainstream of society through the lives of Masons, is a tremendous and awe-inspiring force.

We might look upon our Brother Paul Revere (Grand Master 1795-97) as a dream of vast human schemes. His aspirations were for the betterment of mankind. He was what Henry James called the "absolute genius from whose thoughts and deeds the future flows inexorably." Had Revere not lived, would America be independent? Like Daniel Webster, he was a steam engine in short pants; a superb professional without formal education, but possessing a volcanic inner drive that propelled him on when others chose to halt.

It was his influence, his deeds upon time that assures Paul Revere a special niche in time. He was a skilled, imaginative, and dynamic practitioner of varied crafts, an executor of other people's designs — independence! He was unique, the like of which we shall never know again. The nation needed a hero in the Civil War year of 1863. Longfellow provided a legend whose enduring significance, while perhaps embellished in poetry, will last until time shall be no more.

THE PAUL REVERE URN

At a special meeting of the Grand Lodge January, 1800, it was voted inexpedient for the Grand Lodge to join in the civic funeral procession and ceremonies in memory of the departed George Washington. But, at the same meeting, two committees were raised; one to prepare a suitable memorial for Brother Washington and the other to request of Madame Washington a lock of the General's hair to be placed in a golden urn and preserved among the jewels and regalia of Grand Lodge. Mrs. Washington complied with the request and the hair was placed in a beautiful small gold urn fashioned by Brother Paul Revere. Since that day the urn, with its precious contents, has been one of the treasures of Grand Lodge and each Grand Master, when he assumes office the first time, has the urn in his personal care. At his retirement on St. Johns Day the urn is handed to his successor with the admonition to guard it well.

LONGFELLOW AND REVERE

Why Longfellow Wrote "The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere"

Written by Vaughn J. McKertich

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow 1854 (47 years of age)

Research material furnished by Mr. Frank Buda, Chief of Visitors Service, National Park Service, Longfellow Historic Site, Cambridge, Mass.

Men close to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow were giants in American life, among whom was Brother Josiah Quincy of St. John's Lodge, Boston. He was President of Harvard College, a United States Congressman, and Mayor of the City of Boston.

When a Mason reads Longfellow's stirring epic of Paul Revere's famous ride he senses the Masonic connection. Yet, Longfellow was not a member of the Craft. Masons recognize the five points of fellowship working, one of which is ... "to give timely notice to ward off approaching danger."

Longfellow as a native of Portland, Maine, came to Cambridge in 1836 and occupied the house that served as the headquarters for General and Brother George Washington during the siege of Boston, July 2, 1775, to March 17, 1776. The Harvard professor-poet had a direct family linkage to the American Revolution and a close relationship with Masons and their memorials. He had a sense of Masonic preparedness, again found in the five points of fellowship ... "to go out of our way to assist and serve a worthy Brother."

In the year prior to the outbreak of the Civil War, Longfellow wrote the story about Paul Revere in an effort to reach the people who were in need of a hero. He wrote it in simple, easy-to-understand language for the "countryfolk," which many mistook for a story only for school children.

Research has revealed that in early April, 1860, Longfellow and George Sumner, brother to United States Senator Charles Sumner, a strong abolitionist from Massachusetts, toured the Old North Church. They climbed to the belfry where the bells hung, surprising the pigeons who had found a peaceful haven. Longfellow's poem has probably been learned by more schoolchildren than any other poem written in the English language. "The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere" wasn't finished until October 13, 1860. Said Henry W. L. Dana, grandson of the poet, "The visit to Old North Church with George Sumner probably led directly to the writing of the poem. In a Boston Globe article published Sunday, April 10, 1942, Dana revealed: "In Longfellow's diary there appears this entry: 'April 4, George Sumner at dinner. He proposes an expedition to the North End or old town of Boston.' On April 5 the trip was made."

The poem was first published in the January, 1861, Atlantic Monthly. In 1863 it appeared as one of the Tales of A Wayside Inn. The poet had been interested in that period of the American Revolution because of his grandfather, General Peleg Wadsworth, of whom he held a fondness and from whom he had heard stories. As a young officer, Peleg Wadsworth had served under General Washington and he may have been a Mason, as were most of the members of Washington's staff. In 1842, six years after Longfellow had moved into Craigie House, Charles Dickens breakfasted with the poet. Longfellow took the British author on a 10-mile walk through the North End, during which they visited Copp's Hill Burial Ground and Old North Church. They talked about Revere's written account of his April 18, 1775, ride, possibly to use that dramatic episode as material for a poem. While some Masonic historians are still researching to link Samuel Adams and others of his day to the Craft, we are sure that Paul Revere, John Hancock, Joseph Warren, John Pulling, and others were actively engaged in Masonry and the events leading to the American Revolution. Their lives and deeds exemplified the best in the Spirit of Freedom which the poet Longfellow put into simple understanding words in his, "The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere."

TROWEL, 1984-1985

These articles were written by Edith Steblecki, Associate Coordinator of Research and Programs at Revere House, Boston, to celebrate the 250th anniversary of the birth of Paul Revere.

From TROWEL, Winter 1984, Page 27:

1784 marks the 250th anniversary of the birthday of Paul Revere (1734-1818). It is an appropriate time to reflect upon Revere's accomplishments and also to examine a significant aspect of his life - his career as a Freemason. Freemasonry was officially organized in the American Colonies by Henry Price only two years before the birth of Revere. A survey of Revere's Masonic involvement highlights, not only the story of Masonry in Massachusetts, but also the life and character of Revere himself.

Freemasonry was a fraternity, based upon the medieval stonemason's guilds, which used the tools and biblical legends of the mason's craft to instill a system of morality in its members. By Revere's day, the transition from craft organization to social institution had already been made and Masonic lodge bore little actual connection with the building trade. Established in England in the early 18th century during an age of religious and political diversity and social change, modern theoretical Freemasonry was a useful organization which acted as an agent of stability to promote a sense of global fraternity and moral responsibility, combining the conviviality of a club with higher moral and benevolent purposes, Freemasonry attracted men from all walks of life.

The fraternity transferred easily to the American shores, providing colonists with a special connection to the Mother country, but it should be noted that Masonry was not a strictly conservative institution. At least by the revolutionary era, Masonic lodges contained men of both radical and loyalist political views. Systematic evaluations of membership of 18th century lodges have been few, but recent studies of Genesee County, New York, by Kathleen Smith Kutolowski, and of Connecticut, by Dorothy Ann Lipson, have revealed that, while membership was diverse, Masonry tended to attract those mobile, politically active men, many with commercial interest, who often held positions of leadership in their communities. Revere had much to gain by joining these men. Masonic membership broadened his circle of acquaintances, brought customers to his shop, and gave him continuous opportunities for recreation, companionship and leadership.

Revere enjoyed a long Masonic career which involved three Boston lodges and lasted nearly fifty years. He was probably familiar with the fraternity before he joined, having served during the French and Indian Wars under Richard Gridley with a regiment that included the Masonic lodge of Lake George, chartered May 13, 1756. Revere's service with Gridley, at the age of twenty-one, may have gained him his first exposure to Freemasonry. Four years later, in 1760, Revere was initiated into St. Andrew's Lodge.

Being an artisan like most of the men in St. Andrew's Lodge, Revere and his business soon profited from Masonic affiliation. Revere was a goldsmith by trade, working in both silver and gold, having apprenticed under his father. The first sale recorded in his accounts in 1761 was that of a "Free Masons medal," followed by a several orders for a "Masons Medal for a Watch" in 1762. During his years as an active Mason, Revere also made officers' jewels, ladles and seals, as well as engraving certificates and notifications. Revere also enjoyed the patronage of fellow Masons for non-Masonic gold and silver items. Immediately after the Revolution, Revere also opened a hardware store and his account books reveal, for both the goldsmith shop and the hardware store, that nearly half his customers were Masons. Although Revere must have been aware, as a young craftsman, that he might derive long term financial benefit from Masonic affiliation, it is unlikely that this was his only reason for joining the fraternity.

The benefits that Revere gained from Masonry were amply repaid in loyalty and service. After his initiation in 1760, Revere attended meetings faithfully. St. Andrew's Lodge held twenty-six meetings in 1761 alone and Revere attended all but one. His attendance remained consistent until interrupted by the Revolutionary War. Revere's service as a Lodge officer was also regular throughout his career. Between 1762 and 1797, there were only four years when Revere was not holding one or more Masonic offices. He earned his first office in St. Andrew's Lodge as Junior Deacon in 1762, followed by that of Junior Warden in 1764, Senior Warden in 1765, and Secretary for two years in 1768-1769. He was finally elected Master for the year 1771.

Revere gained additional opportunities for leadership when he took part in the founding of the Massachusetts Grand Lodge in 1769. Prior to that, Boston had only one Grand Lodge called St. John's, a modern Lodge which had received its charter from the Grand Lodge of England in 1733. Since St. Andrew's Lodge was an ancient Lodge and had been chartered by the Grand Lodge of Scotland, St. John's refused to recognize its legality, forbidding Masons to visit "the meeting (or the Lodge so called) of Scotts Masons in Boston, not being regularly constituted in the opinion of this (Grand) Lodge...."

The resulting tensions prompted St. Andrew's Lodge, in conjunction with several other ancient Lodges in Boston, to petition the Scottish Grand Master for its own Grand Lodge of Ancient Masons in America. Under a commission dated May 30, 1769, Joseph Warren, a friend of Revere's and a radical leader, was appointed the Grand Master of the Massachusetts Grand Lodge, with Revere serving as Senior Grand Deacon. Revere continued in this office from 1770 through 1774.

As tensions mounted between Great Britain and her American colonies, Boston soon became the center of rebellion. Both Revere and Warren were heavily involved in radical activities. Masonic meetings may have helped to spread revolutionary ideas, but it should be noted that not all Masons were radicals. Tradition tells us that Revere and other Masons from St. Andrew's Lodge dumped tea into Boston harbor during the famous Tea Party of December 16, 1773, and that the regular meeting of the Lodge, scheduled for that evening, had to be adjourned "on account of the few members present." The Green Dragon Tavern, also owned by St. Andrew's Lodge, housed many political meetings. Nevertheless, there were many Masons who viewed the Tea Party and the Revolution with regret.

While Revere, in his own words, was "employed by the Selectmen of the Town of Boston to carry the Account of the Destruction of the Tea to New York," Mason John Rowe was writing that he was "sincerely sorry for the event" which he believed "might... have been prevented." Due to his special mission, Revere was not present at the Grand Lodge meeting on December 27, 1773. Despite his absence, he was again chosen Senior Grand Deacon for the following year. In 1774, Revere was again riding as a courier for the radical cause. In the fall, he rode to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia with the Suffolk Resolves, written by Joseph Warren. This activity interrupted his regular Lodge attendance. Between August and December 1774, Revere attended only one meeting of St. Andrew's Lodge, while missing both meetings of the Massachusetts Grand Lodge in September and December.

After the Battles of Lexington and Concord, April 19, 1775, on the eve of which Revere made his famous midnight ride, Masonic activity ceased. The Massachusetts Grand Lodge noted that "Hostellitys Commenc'd between the Troops of G. Britain and America, in Lexington Battle. In consequence of which the Town was blockaded and no Lodge held until December 1776." St. Andrew's Lodge also records no formal meeting until April 1776. After the British evacuation of Boston in March 1776, Revere was commissioned as a major in the regiment raised for Boston's defence which was stationed at the garrison on Castle Island in Boston Harbor. Revere served under Colonel Thomas Crafts, a fellow Mason from St. Andrew's Lodge, and soon became a lieutenant colonel. In 1779, Revere participated in the ill-fated Penobscot expedition to dislodge a British fort from Castine, Maine. Although Revere did not have an extensive military career, it was enough to distract him totally from his goldsmith work. From 1775 to 1780, his accounts for the shop record not a single business entry. Due to military obligations, he also missed many Lodge meetings, but he still continued to hold Masonic offices.

Both St. Andrew's Lodge and the Massachusetts Grand Lodge reconvened by 1777. Although the military action had moved away from Boston by this time, the hardships of war were still apparent. Even the Green Dragon Tavern was nearly turned into a hospital by the occupying British. In the spirit of Masonic charity, collections for the poor were taken and "strange brethren," even British prisoners of war, were assisted.

From TROWEL, Spring 1985, Page 27:

Before the war's end in 1783, Revere served as Master of St. Andrew's Lodge 1778, 1779, 1781, and 1782. Although expressions of political sentiment are nonexistent in Lodge minutes, the Brethren of St. Andrew's Lodge did not bother to hide their animosity on one sion in 1778 when they assisted a "Dutch Young Gentleman who was taken by one of Tyrant George's Frigates and had everything taken from even to his certificate . . ." Also while Revere was Master, the Lodge aided a British prisoner of war "as a Token of Love and friendship this Society has for one of the Fraternity tho' an Enemy." Revere also served the Massachusetts Grand Lodge throughout this period, as Junior Grand Warden from 1777 to 1779 and as Senior Grand Warden between 1780 and 1783.

By the war's end, Revere's Lodges were in a state of flux. The Massachusetts Grand Lodge lost its appointed Master when Joseph Warren was killed the Battle of Bunker Hill in 1775. Rather than wait for the Grand Lodge of Scotland to appoint a new Grand Master, the Massachusetts Grand Lodge selected its own leader in 1777, who was repeatedly re-elected throughout the war years, f 1782, the Massachusetts Grand Lodge took a bold step which would alter Revere's future as a Mason. A committee had been appointed, which included Revere, to determine the authority of the Massachusetts Grand Lodge. The committee justified the independent election of the new Grand Master on the grounds that, without a leader, the Lodges "must cease to Assemble, the Brethren be dispersed, the Pennyless go unassisted, the Craft Languish & Ancient Masonry extinct in this Part (of the) World. . ." Their appointment of a new Grand Master was clearly an action of self-preservation. However, the committee went on to resolve that ". . .This Grand be forever hereafter known & called by the Name of the Massachusetts Grand Lodge of Ancient Masons, that it is free and Independent in its Government & Official Authority of any Grand Lodge or Grand Master in the Universe. . . " With this bold resolution, the Massachusetts Grand Lodge declared its complete independence from the Scottish Grand Lodge in 1782.

The 1782 report, signed by Revere with three other Masons and approved by the Massachusetts Grand Lodge, posed a serious question of allegiance for ancient Masons. St. Andrew's Lodge would be forced to decide whether its loyalty remained with Scotland or with the newly independent Massachusetts Grand Lodge. When a vote was finally taken in 1784, half of St. Andrew's Lodge wished to remain loyal to Scotland while the remainder desired to affiliate with the Massachusetts Grand Lodge and the new nation. Revere voted with this second group, which was the minority, and found himself ousted from the Lodge that he had served as Master just two years earlier; but he was not alone. Rejected but not discouraged, Revere and twenty-two fellow Masons founded a new Lodge, also called St. Andrew's, which was chartered by the Massachusetts Grand Lodge. Its name was changed to Rising States Lodge in October 1784. Revere served the Lodge as Treasurer from 1784 until 1786, and as Master in 1787, 1788, 1789, 1791, 1792, and 1793. Due to incomplete records, Revere's additional activities in Rising States Lodge cannot be determined. Directly after the war, Revere devoted most of his Masonic attention to that Lodge. In the Grand Lodge, he served as Deputy Grand Master in 1784-1785 and then held no office until his re-election to the same office in 1790 and 1791.

The climax of Revere's Masonic career came in 1794 when he was elected Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts, the most prominent Masonic position in the state. His election came only two years after the union of St. John's and the Massachusetts Grand Lodges, an event in which Revere also played a part. The union brought together twenty-two constituent Lodges under the newly united Grand Lodge, to which Revere added twenty-three more during his three-year term (1795-1797). In 1795, he also had the honor of laying the cornerstone for Boston's new State House during a Masonic ceremony. A fellow Mason, William Bentley, wrote in 1796 that "Col. Revere enters into the Spirit of it, and enjoys it," while Revere himself admitted that serving as Grand Master was the "greatest happiness" of his life. Ironically, Revere was not the first choice for Grand Master in 1794 but the second. Nevertheless, he fulfilled his office with dedication and skill, ever concerned with the quality of Masonic candidates, the preservation of traditions, and the growth of the fraternity. In 1797 he closed his term with an address "in which his abilities in the Masonic art were eminently displayed."

Revere remained active with the Grand Lodge until 1800, after which time his name almost disappears from Masonic records. This decrease in activity coincides with Revere's establishment of a copper-rolling mill in Canton, MA, which business probably diverted his attention from Masonic work. A golden urn, crafted for the Grand Lodge in 1801 to preserve a lock of the late George Washington's hair, was Revere's last conspicuous Masonic contribution. Between 1800 and 1810, Revere attended Grand Lodge meetings only occasionally. It is difficult to determine the extent of his further involvement with Rising States Lodge, although it is likely that he also diminished or entirely ceased his activities with that Lodge after 1800.

A disturbing end to Revere's Masonic career came in 1810 with the dissolution of Rising States Lodge. Investigations conducted by the Grand Lodge into its causes revealed that the Lodge had been suffering from internal conflicts for several years. In addition, when the members of Rising States Lodge voted to dissolve the Lodge, they also voted to divide the Lodge funds among themselves, rather than deliver the money to the Grand Lodge as ought to have been done when the charter was surrendered. The Grand Lodge finally concluded that the members of Rising States Lodge who noted to dissolve did so with honorable Intentions, only because the Lodge was no longer fulfilling its stated Masonic purposes. It was also shown that the funds received by Revere and others here used for the relief of fellow Masons. Although Revere was cleared of any fault in the event, it must have disappointed him to witness the deterioration of a Lodge which he had helped found twenty years earlier.

Paul Revere died in 1818 at the age of eighty-three. No Masonic mourning greeted his death and he did not even receive a Masonic funeral, but his service in the "cause of humanity, of Masons and of man" — to quote Revere himself — has not been forgotten. An ordinary citizen, Revere was rescued from obscurity by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's famous poem Paul Revere's Ride and he is once again respected for his many accomplishments. He served the fraternity well during a period of great growth and turmoil, and he also contributed to America's infant industrial movement as the crowning achievement of a long and productive life. Despite the legends which surround him, Revere is appropriately remembered today as a noteworthy patriot, craftsman, industrialist, and Freemason.

This story is only a brief sketch of Paul Revere's Masonic activities, based upon research done for the forthcoming publication Paul Revere, Patriot and Freemason, soon to be available from the Paul Revere House. Grateful acknowledgements for assistance in that work must be extended to the staff of the Grand Lodge of Masons in Massachusetts, the Museum of Our National Heritage, the American Antiquarian Society, and the Boston Public Library. Special thanks also to Robert W. Williams III for graciously making possible the appearance of this article.

TROWEL, 1988

From TROWEL, Summer 1988, Page 14:

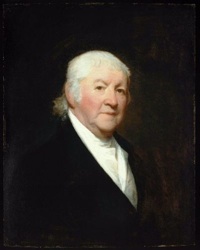

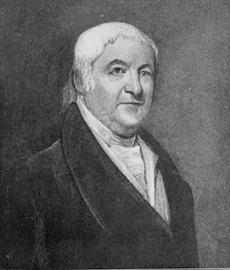

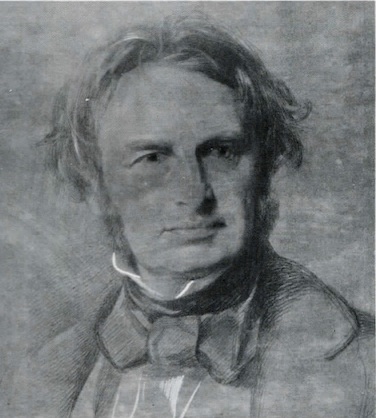

Mezzotint profile of Revere engraved by Charles De Saint-Memin, c. 1800.

Collection, Paul Revere Memorial Association. Photo: John Miller Documents.

Museum of Our National Heritage Exhibits "Paul Revere: The Man Behind the Myth"

The Museum of Our National Heritage, cosponsored by The Paul Revere Memorial Association, with funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, opened an exhibit in Lexington on April 17, to tell and show the real Paul Revere — father, husband, son of a Huguenot immigrant, foundry master, hardware store proprietor, entrepreneur, industrialist, Freemason, and spokesman for Boston mechanics. The opening, coinciding with the 213th anniversary of Revere's famous midnight ride and the 80th anniversary of the PRMA's establishment of his Boston home as a museum in 1908, will be exhibited through March 19, 1989.

Mid-18th Century Saddlebags owned by Revere.

Collection of Paul Revere Memorial Association. Photo: H. K. Barnett.

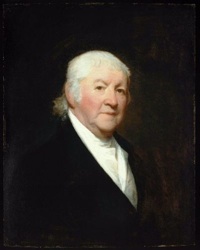

With the stroke of his pen in 1861, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow made Paul Revere into a national folk hero of the American Revolution. Best known for his many famous rides to stimulate the Colonists into a revolution, Revere was also an accomplished silversmith, engraver, jeweler, goldsmith, dentist, and producer of political cartoons opposing the Stamp Act of 1765. At age 33 he sat for portrait artist John Singleton Copley holding the famous Liberty Bowl, now presented to people as a special honor.

Born in Boston in late December 1734, Paul Revere was the second of 12 children of French Huguenot immigrant Apollos Revoire and Deborah Hitchborn, a native Bostonian descended from New England seafarers and artisans. At age 12 he was apprenticed to his father as a silversmith and earned extra money as a bellringer at Old North Church in Boston. As the eldest son (19) he became the supporter of the family when his father died.

Married first to Sarah Orne, in 1757, who died five months after the birth of their eighth child, he married Rachel Walker in 1773. She bore him eight children, the third named Joseph Warren in memory of his Masonic friend who was killed at Bunker Hill while serving as Grand Master of the Massachusetts (Provincial) Grand Lodge. Only four of his 16 children were living when Paul Revere died on Sunday, May 10, 1818. Writing an account of his famous ride to Lexington (April 18, 1775) for the Massachusetts Historical Society at age 63, a year later he designed a tea set for Edmund Hartt, builder of the U. S. S. Constitution. He opened the first successful copper-rolling mill in Canton in 1800, providing copper for the hull of "Old Ironsides" and the roof of the Massachusetts State House for which he laid the cornerstone when Grand Master.

The poet Longfellow deserves credit for making Revere our favorite rebel and folk hero. The successful conspiracy of Masons and non-Masons that sent Revere, William Dawes, and Dr. Samuel Prescott on their famous rides, resulted in the 50 states we now call the United States of America.

The exhibit, "The Man Behind the Myth," displays 200 objects, including the wedding ring for Rachel, made c. 1773; Gilbert Stuart's 1813 portrait of Paul and Rachel, furniture from various Revere residences, family letters and personal items, silver pieces, engravings that include the famous 1770 Boston Massacre scene, and Masonic jewels made by Revere. His business life is illustrated by correspondence, receipts, bills, and account books. More than 30 lenders have contributed to the exhibit, including the Grand Lodge of Masons in Massachusetts.

The Scottish Rite Museum is located at the corner of Massachusetts Ave. and Marrett Rd. (Rte. 2A), Lexington. Hours: Sunday, noon-5 P.M.; Monday-Saturday, 10 A.M.-5 P.M.; closed only Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year's Day.

Kitchen of The Revere House, North Square. Boston. Photo: H. K. Barnett.

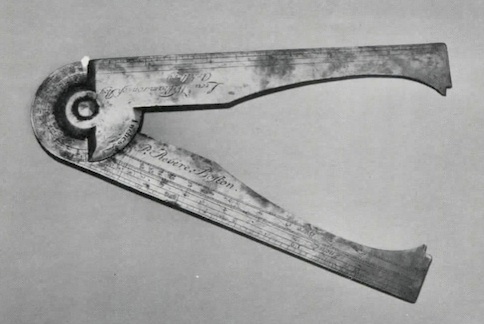

Brass Gunner's Calipers, c. 1770.

Engraved 'P, Revere, Boston" and "Lieu't Williamson of Roy'I Artillery."

Collection, Paul Revere Memorial Association. Photo: H. K. Barnett.

Rear View of Paul Revere House, North Square. Boston.

Courtesy The Paul Revere Memorial Association.

TROWEL, 1996

From TROWEL, Spring 1996, Page 29:

Paul Revere: Mason, Patriot, Businessman, 1735-1818

by R. W. James T. Watson, Jr.

Paul Revere was a man of varied talents. The son of Apollos Rivoire, a Huguenot immigrant, and Deborah Hitchborn, of an old Boston family. Revere learned goldsmithing from his father, who had worked with Boston's finest silversmith, John Coney. But he was also a lieutenant of artillery at Fort Edward on Lake George, was one of the "mechanics" who watched the movement of British troops in Boston and engaged in several businesses: dentistry. copperplating. merchandising, cannon and bell pouring and copper rolling.

While Revere is remembered today for his rides to Lexington and Concord, his greatest contribution to the war effort lay in the production of gunpowder. When Washington assumed command of the Continental Army, he had only 32 barrels of gunpowder and no operating powder mills in the area. He assigned to Revere the task of learning to make powder and building the mill.

In spite of helpful references from James Otis and Robert Morris to Oswell Eve, who had the finest powder mill in the Philadelphia area, Revere was whisked through the mill, not allowed to examine machinery, question the workmen or Eve himself. A disappointed Revere sought the help of Samuel Adams, who within a month produced a plan of one of Philadelphia's powder mills, probably Eve's own.

The work on Revere's mill began in January, 1776, and by May was in production. It was built at Revere's copperplating plant at Canton on the Neponset River, out of the range of the British in Boston. By September it had produced 37,962 pounds of powder and 34,155 pounds of saltpetre. Revere produced most of the powder for the Northern Army until 1779. when the mill blew up, the common end of all powder mills of that era.

Paul Revere was initiated in St. Andrew's Lodge on September 4, 1760, the first candidate received after the charter was granted by the Grand Lodge of Scotland, raised January 27, 1761, and installed master November, 1770. He served Massachusetts (Provincial) Grand Lodge as Junior Grand Warden in 1777, and continued in that position from 1777-1779 when it became Massachusetts (Independent) Grand Lodge.

When Massachusetts Grand Lodge declared its independence, March 8, 1777, not all members of St. Andrew's were in favor. It was voted 30 to 19 to remain loyal to the Grand Lodge of Scotland. The 19 who favored independence, led by Paul Revere, met as a Lodge first as St. Andrew's and later as Rising States Lodge. Revere was Senior Grand Warden from 1780-1783 and Deputy Grand Master in 1784, 85, 91 and 92. On December 8, 1794, when John Warren was elected Grand Master but declined, Revere became the second Grand Master after the union, serving from December 12, 1794 to December 27, 1797.