ChungHua

Contents

- 1 CHUNG HUA, SHANGHAI

- 1.1 NOTES

- 1.2 THE FOURTH LODGE IN SHANGHAI

- 1.2.1 BEGINNINGS

- 1.2.2 FAILURE TO COMMUNICATE

- 1.2.3 MANEUVERS

- 1.2.4 “NOT THE OPPORTUNE TIME”

- 1.2.5 “WE HAVE NOT HEARD THE LAST OF THIS”

- 1.2.6 WATCH AND WAIT

- 1.2.7 THE ANTICIPATED OFFICIAL VISIT

- 1.2.8 “WE HAVE WEATHERED SEVERE STORMS”

- 1.2.9 “A VERY LIVELY INTEREST”

- 1.2.10 THE DECISION

- 1.2.11 AFTERMATH

- 1.3 LINKS

CHUNG HUA, SHANGHAI

Location: Shanghai, China

Dispensation presented to: Herbert W. Dean, August 1920.

Current Status: dispensation declined, 08/12/1930

NOTES

ORGANIZATION OF LODGE, SEPTEMBER 1928

From New England Craftsman, Vol. XXIV, No. 1, September 1928, Page 16:

A new Masonic lodge, known as "Chung Hua" Lodge, somewhat along the lines of the "International" Lodge in Peking and the "Hykes Memorial" Lodge in Tientsin, has recently been organized in Shanghai, the membership of which will include foreigners of various nationalities, but which will be predominantly Chinese.

Owing to the presence of a considerable number of Chinese in Shanghai who have become Masons in America and England, there has been a demand for a Chinese lodge for a considerable period. Since the new lodge desired to become affiliated with the Massachusetts Masonic Constitution, it was necessary for the new organization to obtain the approval of the three Shanghai lodges under that jurisdiction, the "Ancient Landmark," the "Shanghai" Lodge and "Sinim" Lodge. It is understood that this approval has now been granted so that the organization of the new lodge will shortly become an actuality. It will be possible for members belonging to the older lodges to also become members of the Chung Hua Lodge. The new lodge at first considered affiliation with the Grand Lodge of the Philippine Islands, but later decided to affiliate with the Massachusetts organization. — From the China Weekly Review.

THE FOURTH LODGE IN SHANGHAI

Rt. Wor. Walter H. Hunt

Grand Historian, Grand Lodge of Massachusetts

The story of Chung Hua Lodge scarcely receives a mention in the Proceedings of our Grand Lodge. The decision to decline the petition for dispensation is mentioned - not by name - on pages 349-350 of the 1930 Proceedings, as a part of Grand Master Dean's report on his journey to China in the spring and summer of that year.

The story is a long one, and well-documented; it ends in 1930, but begins more than three years earlier, in 1927. At that time there were eight lodges under Massachusetts jurisdiction in China, the oldest three in Shanghai. Freemasonry in China was on the rise; in the last five years, four lodges in other cities had been chartered. There were other jurisdictions operating in China, and in particular in Shanghai, including England, Scotland and Ireland.

It would have seemed logical for a new lodge to be introduced, in order to help defray the costs of the proposed new Temple. But a fourth lodge met with fierce resistance, uncovering biases and evoking fears that made it clear what European Masons – and Europeans in general – thought of the native Chinese. It does not cover the Craft with glory, but as it is part of our history, it deserves our attention.

BEGINNINGS

The first evidence of interest in the establishment of a new Lodge is a letter written in May 1927 by Wor. Thurston R. Porter, Master of Shanghai Lodge, to Wor. Walter F. W. Taber, Past Master and Secretary of St. John's Lodge in Boston.

“There is on foot in Shanghai a movement to establish an international lodge,” he wrote. “The formation of this body is being opposed by the members of Shanghai Lodge, for which you hold the proxy . . . There are now three Massachusetts lodges in this city.

"Ancient Landmark and Shanghai Lodge, so far as I can ascertain, never have balloted on Chinese; Sinim Lodge has a few among its membership. For more than a year, the idea of having a Masonic organization of their own has been in the mind of some local Chinese. Last summer, when I was serving as Senior Warden of Shanghai Lodge, I was approached by Hua Chuen Mei, a member of Sinim Lodge, who spoke of this plan . . . five weeks ago, when Bro. Mei called me by telephone and asked that I attend a meeting he had arranged at which the plan was to be discussed, I told him I could not attend because the Lodge had not authorized me to do so.” According to Wor. Bro. Porter's account, the Chinese-only lodge idea had been replaced by an "international" organization for both Chinese and American Masons. Members of Shanghai Lodge had been appointed to a committee to pursue a dispensation, “without,” he noted, “the consent of the Master thereof or any reference to our Lodge.” With the recent ‘troubles’ in China, he thought it unwise and thought that it had delayed the plan but felt that “the request for a dispensation and charter doubtless will be made sooner or later.”

Shanghai Lodge adopted a position of opposition to the establishment of a new Lodge by formal resolution in April 1927, though at the time the idea of a purely Chinese lodge was being contemplated. Still, Porter observed that Shanghai Lodge had nearly surrendered its charter in 1924 due to a severe decline in membership; but it had raised 30 new Masons since then, and had acquired members of other Lodges. Still, he said, “Every ship leaving Shanghai at the present time is filled to capacity with people on their way home, and, of these, 75 per cent may not return.” Shanghai was a “unique city in its internationalism. We have here all the races of the world” and all of the Masonic constitutions worked harmoniously. The other jurisdictions were unalterably opposed to admitting Chinese, and any “Chinese lodge (call it international, if you will)” would divide Massachusetts Masonry from the others.

Porter's letter continues in a rather politically incorrect way in his description of the Chinese culture and temperament, making no secret of his (and his lodge's) disdain for the idea of raising Chinese Masons, and he directs Bro. Taber, as proxy, to oppose “the granting of even a dispensation to this proposed international lodge.” Copies of the letter were furnished to the District Grand Master, Rt. Wor. Bro. Irvin V. Gillis, and the Grand Secretary, Rt. Wor. Bro. Frederick Hamilton, along with a copy of the resolution from Shanghai Lodge, sent to District Grand Secretary Bro. Conrad Anner by Bro. H. W. Strike, secretary of the Lodge.

The returns for 1927 were not included in the Proceedings that year (though there is a report from the District Grand Master filed later; see below); but in the 1928 recapitulation, nearly 700 Masons are recorded: 89 in Ancient Landmark, 81 in Shanghai and 201 in Sinim in the city of Shanghai; 139 in International Lodge in Peking; 18 in Talien Lodge in Darien in Manchuria; 103 in Hykes Memorial Lodge in Tientsin; and 35 in Pagoda Lodge in Mukden in Manchuria. An eighth lodge, Chin Ling in Nanking, was in being in 1927 but due to local conditions had ultimately lost its charter in 1928. In short, the numbers were very modest. By comparison, China was huge: it had nearly 486,000,000 inhabitants in 1927. It was also in the midst of turmoil at a scale that Americans, at least, found difficult to understand or accept: violent incidents at Nanking and Hangchow were very recent in memory, leading to the departures that Bro. Porter described in his letter.

The Grand Secretary and Grand Master replied in brief, acknowledging the receipt of the letters from various sources. Brother Hamilton observed in a letter to Brother Anner that “the Brethren in Shanghai may rest assured that the Grand Master will do nothing which would be fairly regarded as contrary to the best interests of Masonry in Shanghai.” The Grand Master, Most Wor. Bro. Frank L. Simpson, wrote to Wor. Bro. Taber, Shanghai Lodge’s proxy, to say that he had ‘nothing pending’ and doubted whether a petition would even be submitted – indeed, he would take no action until it was placed before his District Grand Master for his consideration.

THE DISTRICT GRAND MASTER’S REPORT

In the fall of 1927, Rt. Wor. Bro. Gillis made a thorough report of affairs in the China District. He wrote as follows regarding Chinese nationals in lodges under the Massachusetts constitution:

“Sinim Lodge is the only Massachusetts Lodge in Shanghai that has received Chinese. For some four years, up to the last year, one or two carefully selected Chinese were initiated this year. The general political situation in China during the past two years has undoubtedly had definite and unfortunate reaction to the question of making Masons of Chinese. At the present time, we have to face the fact that further initiations are not possible even in Sinim Lodge.

“About a year ago, several Chinese Brethren got together and formed a committee looking forward to the organization of another Lodge in Shanghai that would be definitely international in character . . . It was decided . . . that the brethren of the three Lodges in Shanghai should be informally sounded out with respect to their views . . . in Shanghai Lodge, the question came up in open meeting . . . there is no doubt that at the present time, a petition for the formation of an international Lodge, which would receive Chinese into its membership would not meet with favour among the Shanghai Lodge brethren.

“So far as your Deputy can determine, Ancient Landmark shares much the same views . . . In Sinim Lodge the feeling is undoubtly {sic} more favourable to the idea . . . To sum up, with respect to our Chinese friends, we have to admit that at the present time the outlook is not favourable.”

Irvin V. G. Gillis, District Grand Master

Rt. Wor. Irvin Van Gorder Gillis, District Grand Master in China, was a very forthright, no nonsense man. He had been raised in International Lodge in Peking in 1916, and had been the Grand Master’s personal representative since 1922. He had been in China for more than thirty years, both as an attaché for the U. S. Navy and as a businessman. He had married a Chinese woman and was fluent in Mandarin.

If anyone understood what he called the “Shanghai Mind” – at least from a Western point of view – it was he, and by declaring in his official correspondence with the Grand Lodge that he thought the matter unlikely to bear fruit, he certainly believed that it was a dead letter. In this respect, he could not have been more wrong.

Attached to the District Grand Master’s report was a letter addressed directly to the Grand Master, in which he commented extensively upon the proposed fourth Lodge in Shanghai. In these remarks he is much less diplomatic than in his official report.

“There has been considerable agitation during the past year for the formation of another lodge under the Massachusetts Constitution at Shanghai . . . this was started by certain Chinese brethren with the intent that membership would practically be limited to Chinese, but failing support they apparently took the matter up with some of the foreign brethren, and {most} . . . were members of Sinim Lodge. The ostensible desire was to form a lodge in which Chinese would be more readily and agreeably received . . .

“I have had several letters on the subject from individual brethren at Shanghai in opposition . . . The present “rights recovery” spirit would soon bring about an influx of undesirable Chinese into the lodge who would seek to join and enter from unworthy motives, - of this, I feel certain. The original group of foreign masons would in less than no time be swept out of all influence and control, and then the end would come.”

He also attached a descriptive document entitled “The So-Called Chinese Grand Lodge”, written by Wor. W. B. Pettus, a Past Master of International Lodge, describing an organization called the Chih Kung Tang or “Public Weal Association”, which bore the English translation of “Chinese Free Masons” on its outside sign on Avenue Haig in Shanghai. The document dismissed the idea that this organization was Masonic, as it failed most of the Ancient Landmarks, including the lack of monotheism, a volume of sacred law upon the altar, symbolism of the operative art, and admission of women. This report was reprinted in full in the 1928 Proceedings, as part of the Quarterly Communication.

FAILURE TO COMMUNICATE

Our modern communications make us somewhat oblivious to the logistical obstacles in being most of a century ago. Postal correspondence took three to four weeks to travel from China to Massachusetts; indeed, the sheer size of the China District made the logistics of the District Grand Master’s duties a difficult proposition. Bro. Gillis was located in Peking, more than 1,200 kilometers distant from Shanghai; accordingly, much of the direct interaction with the Shanghai lodges was in the charge of his Deputy District Grand Master, Wor. Arthur Quinton Adamson, a Past Master of Sinim Lodge. Brother Adamson was a Quaker, born and raised near Ankeny, Iowa; he was trained as an engineer, and had come to China to oversee an extensive building project in Shanghai and elsewhere in China for the YMCA. He had been raised in Sinim in the same year as Bro. Gillis, and had served as Master in 1922. He was among those who favored the erection of a new lodge in Shanghai to admit Chinese, which ultimately led to some communication issues that would erupt into controversy during the spring and summer of 1928.

At the spring Quarterly Communication of Grand Lodge, Wor. Bro. William B. Pettus made a formal presentation of his paper on the “so-called Chinese Grand Lodge”, as described above; and while visiting in Boston, he had a conference with Rt. Wor. Bro. Hamilton, the Grand Secretary, and Most Wor. Bro. Simpson, the Grand Master. The two came away from the discussion with the impression that the opposition to the new lodge derived from Shanghai Lodge only, and the Grand Master wrote to Bro. Gillis indicating that he might be willing to grant the dispensation if Gillis endorsed it, whether Shanghai Lodge objected or not.

At the same time, Bro. Hamilton wrote another letter to Wor. Bro. Adamson – ostensibly in his role as proxy for Ancient Landmark Lodge, rather than as Grand Secretary – to sound him out on the subject of the new lodge. He wrote:

“I am afraid that there may be some opposition to this [the new Lodge in Shanghai] on the part of the existing Lodges in Shanghai. If such opposition existed I suppose it would be based on two points. First, the fear that the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts might charter lodges made up entirely of Chinese. . . [second] the rigidity with which the English in Shanghai appear to disposed to draw the color line.”

To the first, he assured Bro. Adamson that the Grand Lodge had no intention of creating Chinese lodges; to the second, after noting that the Grand Lodge had no intention of telling any lodge whom it should or should not admit, but “Masonry may afford a most important point of contact between Americans of light and leading Chinese . . .” and that Massachusetts could do in China what the Grand Lodge of England was attempting to do in India, to provide a "platform of understanding and sympathy" in a place where society was somewhat in unrest. Accordingly, Hamilton hoped that Adamson might be able to help “allay the fears and remove any possible opposition among the lodges in Shanghai.”

It is clear from the subsequent correspondence that Bro. Adamson was encouraged by Bro. Hamilton’s opinions on the subject, and that those brethren in Shanghai favorably disposed to the new lodge would receive a positive hearing when the petition was finally presented. This was in stark contrast to the position held by Bro. Gillis, who would soon learn about this correspondence between Hamilton and his deputy.

MANEUVERS

The Chinese brethren had not been idle in the several months since the matter was originally considered. The principal Chinese Mason in the movement, Dr. H. C. Mei, had written a letter to Judge Charles S. Lobingier, representing the Grand Lodge of the District of Columbia; in it he asked advice on how to proceed and – in one form or another – received an indication that he should contact either Lobingier’s Grand Lodge or the Grand Lodge of the Philippines for a dispensation.

When Bro. Adamson learned of these proceedings – quite well advanced, in fact: Dr. Mei and a number of the others involved in the process had already written the request – he asked them to hold off based on his letter from Bro. Hamilton.

On April 19, about six weeks after the March Quarterly and a week or so after Adamson received Hamilton’s letter, he wrote to Gillis informing him of the correspondence and the doings of the Chinese Masons. He noted that Hamilton wanted the Shanghai lodges not to obstruct the creation of a lodge willing to admit Chinese nationals and that he had been urged “to do everything possible to clear up the barriers that existed some time ago.”

It was not the news that Gillis wanted to hear. His response was to send a telegram – in code – to the Grand Secretary’s office on May 3.

“Your undoubtedly well intention but unfortunately ill-advised private letter to Shanghai evidently written with but partial knowledge {of} situation in general . . . {has} been misconstrued and have seriously accentuated aggravated complicated what has always been at the best extremely difficult situation for me to handle . . . I am of opinion that my position has been so weakened {by} your action that it is no longer tenable and my usefulness as District Grand Master is ended . . . kindly refrain from writing further like letter(s) and inform Grand Master of my views of the situation.”

On May 4, unaware of Gillis’ frosty telegram to Hamilton and his superior’s intention to resign over the situation, Adamson forwarded the application for dispensation for Chung Hua Lodge in Shanghai. Ten of the twenty-five petitioners were Chinese, with one of the three principal offices to be occupied by a Chinese Mason (Bro. and Dr. Hua-Chuen Mei as Senior Warden). A few days later he sent a further polite request regarding the design of a seal for the lodge. It should be reiterated that Adamson and Gillis were seven hundred miles apart – and that China was no easy place to communicate in the spring of 1928: their most reliable medium was postal letter, and it was impossible for brethren in Peking and Shanghai to keep up to date on events.

The District Grand Master took until May 14 to compose a reply. He was clearly very distressed at being “out of the loop” on the matter of the new lodge at Shanghai, which he had considered to be a dead letter; still, he granted his deputy the benefit of the doubt, writing that he was “ignorant at the present time of what has been going on, and from your letter of April 19th it would seem that the Chinese brethren concerned have not been very particular” in keeping Adamson informed.

Gillis considered the correspondence with Bro. Lobingier to be “not in order, and to have opened negotiations with the Grand Lodge of the Philippines, while still retaining membership in a Massachusetts Lodge, highly improper.” He censured Lobingier, who unlike the Chinese brethren interested in the petition, should have known better.

“The action of the Chinese brethren has not been open and above-board, and requires more than an off-hand and casual explanation to clear up. Their taking concerted action . . . does not augur well for future ‘internationality’ . . .

“I presume, however, that all of my criticism must have been fully explained away to the complete satisfaction of the foreign brethren [by which he means Western, non-Chinese Masons]; otherwise they would not have associated themselves with the Chinese brethren by signing the petition . . . I take it from what you say . . . that Right Worshipful Brother Hamilton’s letter of March 19th . . . influenced both the Chinese and foreign brethren alike, and naturally by its wording gave them the impression that the setting up of another lodge of an international (Sino-foreign) character at Shanghai met with the full approval of the Grand Lodge . . . with the practical assurance that a dispensation would be granted them if they submitted a petition to the Grand Master . . .

“. . . a careful reading of Right Worshipful Brother Hamilton’s letter reveals that he practically tells you to go ahead in so many words.”

Adamson’s response a few weeks later is carefully worded, but either he is unaware of Gillis’ upset or chooses to ignore it.

The petitioners were not engaging in official communication with the Philippines, he noted, and that Grand Lodge had taken no action: there had merely been some informal discussion through an intermediary (Bro. Sy Cip, whom Wor. Bro. Lobingier had suggested as a conduit for communications). He attached both Dr. Mei’s letter to him, and Lobingier’s letter to Mei – he apparently felt he had nothing to hide from Gillis.

He also noted a suggestion made by a Past Master of Sinim suggesting that the charter could make some restriction requiring fifty percent of the membership of the new lodge to be American, and that he felt that the Chinese brethren would not object to such a clause.

In closing, he noted that his greatest concern was not the granting of the dispensation – his correspondence with Gillis suggests that it was likely to occur, given the approval of Sinim and the approval (without comment) by Ancient Landmark Lodge that month – but rather how the signatures could be safely transmitted to Grand Lodge.

By the end of May, 1928, it was clear that most of the principals – in China and in Massachusetts – had made up their minds on the subject. The next set of letters revealed just how deep the divisions were, and how angry the opinions would become.

“NOT THE OPPORTUNE TIME”

On June 3, Wor. Bro. Thurston Porter wrote a letter to Gillis outlining his concerns about the proposed new lodge. He noted that he did not speak with any authority, as he was no longer an officer of Shanghai Lodge.

After returning from a business trip in Tientsin, Porter learned of the vote of approval held in Sinim Lodge. It was by no means unanimous; it had been accepted by a vote of 33-21, “their meeting being the largest attended they had ever had” (out of a membership of about 200). He also noted that an opponent of the proposal was preparing

“a long letter to our proxy in Boston . . . setting forth the more prominent of his ideas . . . [he] feels that if a Chinese Lodge is organized (and that is what it will be in a short time) our Ancient Landmarks will be in danger, and that to permit this new organization to go through is but storing up trouble for Masonry. In that letter he will point out that the Chinese law prohibits secret societies . . .”

This was an important point, the first time it was raised in the discussions: Bro. Porter, as well as others, would observe that the presence of Chinese nationals made lodges vulnerable to being interrupted (or “raided”) by government officials due to this restriction.

On June 8, the Senior Warden and acting Master of Shanghai Lodge, Bro. E. T. M. Van Bergen, wrote to Bro. Gillis with his opinions on the matter.

“There is a strong opposition here against the formation of this lodge at the present time . . . I have been approached by a number of American Masons, all business men, urging me to do all I can to prevent this lodge being chartered.

“It is being openly said that the promoters are attempting to ‘railroad’ it through . . . that the D. D. G. M. [Adamson] used his office to influence favorable votes, and that its foreign supporters are all missionaries and quasi-missionaries who would make use of Masonry as a means to an end . . .

“My personal opinion is that the matter has been unduly rushed . . . I think it should have gone on the circulars of the three lodges as a matter to be discussed at the meeting and voted on at the next . . .

“There is a danger which I do not think has been thought of . . . the law of the Nationalist Government forbids forming any societies, or holding any meetings, without permission of the Government. This means that the Chinese government could interfere with lodges having Chinese members, and cause them to be raided, even when the meetings are held in the French Concession or International Settlement . . .

“I am not opposed to the principle of having international, and solely Chinese, lodges in China, but until we know definitely what the reaction of the Chinese Government toward such lodges will be, I believe we would be unwise to have any more chartered under Massachusetts Constitution.”

In Van Bergen’s letter to Bro. Taber, the proxy in Boston, he is far more direct.

“This petition was sent to the three Massachusetts Lodges in Shanghai by the Deputy District Grand Master, Wor. Bro. A. Q. Adamson, accompanied by a letter wherein he urged the Lodges to vote favorably for it. Also copy of letter he had received from the Grand Secretary of the same tenor. . .

“The petition was approved by Ancient Landmark Lodge without discussion. Shanghai Lodge discussed it thoroughly and rejected it by a large majority. Sinim Lodge discussed it thoroughly and approved it by 33 votes for and 21 against . . . The foreign Masons who signed the petition are all members of Sinim Lodge, and there are none from Ancient Landmark and Shanghai Lodges thereon, nor have any been approached to do so . . .

“You will recall that Wor. Bro. Porter wrote you when this matter first came up. The situation has not improved in the past two years, and the objections which applied then also apply now. The principle of admitting Chinese into Masonry is not objected to, but the present is not the opportune time for doing so, and until this country has reached a responsible and trustworthy development, we believe that the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts should do nothing to encourage its citizens to enter our Order. . .

“There is nothing to show that they {Chinese citizens} would live up to the Masonic moral virtues of Truth, Charity, Prudence, Temperance, Justice, and Brotherly Love, but ample evidence to prove that they have committed all manner of crimes and violation of obligations in order to save ‘face’ and would not hesitate to betray the secrets of Freemasonry for personal ends, or in revenge.”

Bro. Van Bergen, who was originally from Missouri, was doing his best to convey fair-mindedness in his letter, until he tossed one particularly biting phrase. “Would the Grand Lodge grant a charter to a lodge of American Negroes?” Of course not, he implies . . . “With thirty-five years experience in China, I have no hesitation in stating that I would have more confidence in the average American Negro living up to the moral standards of Masonry, than I would of the average Chinese.” Which is to say, none.

In a subsequent letter later in the month, Wor. Bro. Van Bergen formally protested the involvement of Adamson and Hamilton in the affair.

A similar letter was sent to the District Grand Master by Wor. Bro. Frank D. Drake, Master of Sinim Lodge. He presented what he called a “minority report.” Sinim, he noted, had seven Chinese members, but there had recently been sentiment against the introduction of any others, in part due to ‘incidents’ in Hankow and Nanking. It was felt

“ . . . that we should not encourage additional Chinese applicants . . . possibly until China, as a Republic, has set her house in order and become a recognized government among the Powers. Our Chinese membership, not being satisfied to wait, immediately set out to agitate for a separate lodge. In this effort they were encouraged by Masonic Brethren in the missionary field and the Y. M. C. A. {by which he refers to Bro. Adamson} . . .”

He stressed that if approved, the new lodge would quickly become exclusively Chinese, and that any restriction (such as the one mentioned earlier regarding percentage membership by Westerners) would be opposed by Chinese members; putting it in the by-laws would be to no vail because “by-laws can always be changed by a vote of the Lodge.” Even the threat of withdrawing the charter was irrelevant, since Chinese Masons thus raised would remain members “and can do untold harm if they are so disposed.”

Bro. Drake provided Bro. Gillis with an extended discussion of the Chinese notion of ‘Face’, and that this principle would trump any Masonic obligations. He further reiterated the concern about government officials ‘raiding’ lodges with Chinese members.

In a letter later in June, Bro. Drake informed the District Grand Master that Dr. H. C. Mei, in order to save ‘Face’, had renounced his American citizenship “which came about by accident of birth” in favor of Chinese citizenship. Drake passed on a few questions that Dr. Mei had posed to the lodge regarding the conduct of a lodge toward Brothers in certain circumstances; this was further evidence of unsuitability. “One wonders what is in the mind of this brother who is designated as the first S. W. of this new Lodge and will eventually become its first Chinese Master.”

“WE HAVE NOT HEARD THE LAST OF THIS”

Brother Gillis was now armed with considerable information about the petitioners, the supporters and the tenor of the situation in Shanghai, and on July 12, 1928, wrote a long letter to Grand Master Frank Simpson with his recommendations. It should be noted that he had already implied in his telegram to Grand Secretary Hamilton in March that he intended to offer his resignation in the face of what he perceived to be an undermining of his authority by Hamilton, by Adamson and by the forces that desired a new lodge in Shanghai; now, in excruciating detail, he laid out the case for his own position and his opposition to the erection of the fourth lodge in Shanghai.

“When the matter of setting up a Masonic lodge here in Peking (under the Massachusetts jurisdiction) was under discussion the question of Chinese membership was brought up . . . the admission of Chinese was not only sanctioned, but looked upon with distinct favor as being in line with the landmark of ‘Universality’. Chinese membership was one of the foundation stones of International Lodge and later of Hykes Memorial Lodge, both of which lodges started with one or more Chinese brethren at charter members.”

Shanghai lodges only considered this matter after several years, and even then, “many brethren thought that a mistake had been made,” but that prejudice had been partially overcome. Sinim, the youngest and most active, admitted Chinese, but the other two lodges refused to do so.

“As time went on it became evident to our Chinese brethren that they were not met and their hand grasped with that hearty, cordial, and kindly spirit of fellowship to the extent that they had anticipated . . . In other words that it was not making for Harmony. . .

“These being the circumstances it was but natural that the matter of setting up another lodge where in Chinese and foreigners could meet on the basis of Masonic and social, and particularly racial equality should be given consideration . . . For some little time the movement went forward rather slowly . . . but it was soon evident to the proponents that the movement was not looked upon with favor in general Masonic circles.”

Bro. Gillis then detailed the correspondence and background that had led to the situation as he then saw it. He described the letters of Porter, Drake, Van Bergen, Hamilton, and Adamson, and was particularly critical of Lobingier’s involvement. He also noted that while Sinim and Ancient Landmark had consented to the motion (and Shanghai had rejected it), neither of the consenting lodges had actually approved it. He wrote:

“I am convinced in my mind of two things. First, that this matter has been rushed through the lodges at Shanghai with unnecessary and unseemly haste, without time being given for the brethren to give it the serious consideration that its importance warranted. . . Second, that the Brethren have been unduly influenced by Right Worshipful Brother Hamilton’s letter, as well as by the earnest solicitation and active support of my Deputy, Worshipful Brother Adamson, one of the signers of the petition.”

Though it seems clear that Gillis might have wanted to excoriate both Brothers for their actions, he exonerates them, indicating that he believed that each was doing his ‘Masonic duty’ as he saw it “with the very best of intentions, of course.”

Gillis then set about to educate the Grand Master about China, and the relationship between foreigners and Chinese, based on his quarter-century in the Far East, the last twenty years in China.

“The so-called intellectuals, or intelligentsia, among the Chinese are badly infected with the 'inferiority complex', and as the 'superior' in the comparison is the 'foreigner' this has resulted in 'antiforeignism' to a degree that has never before seen in China. . . In somewhat similar manner antiforeignism is being preached and fostered by the Kuo Min Tang to serve its own ends. First, as a weapon of revenge for what its leaders are pleased to designate as foreign oppression and aggression in the past; and second, to distract the attention of the masses from their own venality and shortcomings."

He then offered a description of the KMT’s ‘Hymn of Hate’ – the “propaganda policy” of the party; the Kuo Min Tang, he explained, or the so-called “Nationalist Party”, translated in English to ‘country – people – association’ – but it was “part of the bluff”, since Sun Yat-sen’s original party was the “Ko Ming Tang”, from ‘ko’, “stripping off or flaying” from the ‘ming’ – the Manchus. He characterized the Kuo Min Tang as the equivalent of Tammany Hall. And what did this have to do with the setting up of a lodge?

“You must know that under Kuo Min Tang rule . . . there is no such thing as ‘personal liberty and individual freedom’ for a single Chinese, nor will there be for a single foreigner if extraterritoriality is abolished. If you are a member of the Kuo Min Tang you are the slave of a tyrannical task-master that brooks no opposition of its will – not even opposition of thought. If you are not a member you have no rights of any kind, you are simply permitted to exist on sufferance.”

A lodge admitting both foreigners and Chinese works under difficult conditions, he noted. “To add to this difficulty by setting up still another lodge in which both Chinese and foreigners will be included seems illogical and the height of folly under the present conditions.”

He anticipates the Grand Master’s reply – why should Masonry not seek to ‘ameliorate the situation’? Because, he says, that this effort must be understood for what it is: “a stepping stone to the formation of an independent Chinese Grand Lodge.” The lodge, if erected, would be a ‘grist mill’ to make Chinese Masons, and when the lodge is crowded, another petition would be made for an additional lodge. Kuo Min Tang members would admit further Kuo Min Tang candidates, and black balling would be insufficient – it would lead to dissension, and ultimately the Chinese would simply establish their own lodges and designate them “Masonic” – with disastrous results for Freemasonry in China.

“Let it be said that I have no right to impugn the motives of our Chinese brethren in the unjustifiable manner that I am doing. So be it. But I am more willing to be accused of this, than I am willing to give my approval and favorable recommendation to the setting up of this new lodge under the present conditions, when such an act may (nay, probably will) reflect unfavorably on American Masonry in general and upon our own Massachusetts Grand Lodge in particular. . .

“Whether the petition is granted by you as Grand Master, or it is denied, I foresee dissension and trouble, but I am of the opinion that there will be less of both and not so much harm done if the petition is denied than there will be if it is granted. . .

“This unfortunate situation did not exist two or three years ago, and has only become acute within the last few months . . . I sincerely hope that the present conditions are but temporary and that all will be well with us Masonically in this District before many months pass by . . . but I am very sorry to say that I greatly fear that the pernicious effects of the Kuo Min Tang “Hymn of Hate” will last not for months, but for years to come.”

He closes his letter by noting that if six brothers in Sinim had voted differently, the petition would have been disapproved, and the situation would not be what it is; and if the petition to the Grand Lodge of the Philippines had been permitted to be sent, it would be their problem and not one for Massachusetts. In any case, he voiced his strong disapproval.

In an accompanying letter, Gillis formally offered his resignation, as he could not in good conscience carry out the “declared policy” he read in Hamilton’s March 19 letter, nor did he believe he could continue to function as District Grand Master as his presence would be disharmonious due to his opposition. But, he warned,

“We have not heard the last of this incident by any means, - either with or without this contemplated new lodge, - and I feel that it is best for all concerned that a new start be made.”

WATCH AND WAIT

Gillis’ letter reached the Grand Lodge in August, roughly a month after he wrote it. The Grand Master took no immediate action, presenting – by proxy – the Henry Price Medal to Brother Gillis at the September Quarterly Communication, and sending a brief telegram during the early part of October: “Have given petition and your letter mature consideration; convinced neither matter should be determined present time; hope both may rest in abeyance for further information and future developments; am writing you fully.”

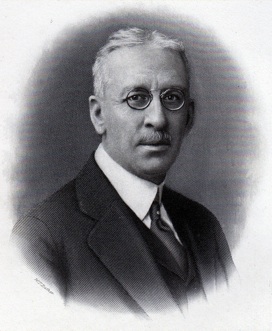

Frank L. Simpson, Grand Master 1926-1928

And, while at his vacation residence in Holderness, New Hampshire, Grand Master Simpson composed a long reply to Gillis’ long letter.

Frank Leslie Simpson served as Grand Master from 1926 to 1928. This situation came to a head just at the end of his third year, as he was preparing to vacate the office. Simpson was a lawyer and scholar, an expert particularly on torts, that area of jurisprudence dealing with liability under the law. He was extremely active during his term, making several rulings regarding candidates, jurisdiction and education; he established the first Lodges of Instruction, and completely redrew the districts in the state (establishing the configuration that would be in place until 2003, when it was replaced by the present arrangement.)

He was, in short, well trained and positioned to examine the case as he might undertake a court procedure, considering all the angles and opinions, in order to make a judgment.

With the correspondence and reports in front of him, he undertook to answer Gillis in detail in a letter dated October 18.

“I found myself subject to conflicting opinions, and came to realize that the matters presented to me for determination were of such importance and difficulty that I certainly ought not to decide them hastily . . .

“I was especially desirous of waiting until I had an opportunity of conference with Wor. Bro. Pettus . . . Conference with him was especially important because of the circumstance that Brother Pettus was here in March and talked with Rt. Wor. Bro. Hamilton about the formation of the new Lodge, and I was informed by Brother Hamilton that he was under the very definite impression that Worshipful Brother Pettus’ advocacy of the new Lodge was stated by him to be in harmony with your opinion at that time . . .”

Which, as it happened, was far from the truth; and when Most Wor. Bro. Simpson received Gillis’ July 12 letter, he was “considerably disturbed and confused.” In his conference with Pettus in September he was told that Gillis was, in fact, in favor of the new lodge, and Hamilton confirmed it. Indeed, the Grand Master was hesitant to criticize Hamilton, who was a figure of some authority and prestige in Massachusetts and in the global Masonic community – and in any case, the letter that supposedly undermined Gillis’ authority was not written from the Grand Secretary’s office, but as an “individual opinion”. This might have been a fig leaf on the part of Grand Master Simpson, but it sidestepped the need to hold Hamilton responsible for problems in the China District. In any case,

“Rt. Wor. Bro. Hamilton understood and had the right to understand from the representations made to him by Worshipful Brother Pettus that his letter to Brother Adamson was quite in accord with your desires. It would appear, therefore, that this whole thing is an unfortunate understanding . . .”

A misunderstanding, indeed: between the Grand Secretary and Pettus, between Hamilton and Adamson, between Simpson and Hamilton, Hamilton and Gillis, Gillis and Adamson . . . and, what was more, the Grand Master indicated, Gillis was incorrect in his interpretation of Hamilton’s letter that the Grand Lodge would endorse a dispensation against Gillis’ own advice.

But ultimately, Grand Master Simpson felt that the decision should not be his to make. Gillis’ arguments against the new lodge were “very cogent and persuasive,” and he would decline the dispensation if “immediate decision” was required – but he had only ten weeks left in his term, and felt that it should be up to the next Grand Master. Similarly, he wanted to postpone any decision about the office of District Grand Master to the next man – but he noted:

“It is very difficult for me to believe, knowing the high standard of your Masonry and the character of the administration which you have given to our affairs in the China District, that your authority can possibly have been diminished . . . I have conferred with Grand Masters with whom you have heretofore been associated and I find no one who agrees with you in respect of your opinion expressed in your letter that your position has become untenable. In any event . . . it seems to me that it would be particularly unfortunate to make a change in the District Grand Mastership at the present time. You have performed your duty conscientiously as you saw it. . . It happens that your performance of duty meets the entire approval of the Grand Master for the time being . . .

“Besides all this, there is no man who is so familiar with the conditions as you are. There is no man who has had the experience you have had, and this is a time when experience is peculiarly important.”

But that decision, also, should lie with Simpson’s successor.

THE ANTICIPATED OFFICIAL VISIT

At the end of October 1928 the putative officers of Chung Hua Lodge hosted District Grand Master Gillis at a lavish dinner at the Bankers’ Club in Shanghai. With his resignation “held in abeyance” (his words, in a telegram to Grand Master Simpson sent late in October after Simpson’s own telegram to him), Gillis listened politely to the arguments for an international lodge in Shanghai. It was an international city, he was told; there were many western-educated Chinese there who desired the sort of fellowship that Freemasonry offered. With most lodges in Shanghai “organized along nationalistic lines”, as a letter from Dr. Mei to Gillis described a few weeks after the event, it made such an international lodge necessary – as a result, not a cause, of what he termed an “international spirit.”

It was clear that no dispensation would be forthcoming from the outgoing Grand Master, but there were indications that the new one might be making an official visit to the China District early in 1929. Accordingly, the would-be petitioners were optimistic about the possibility that, even if the lodge could not be inaugurated during the visit, a dispensation would be forthcoming. One of the petitioners for Chung Hua, Bro. William Yinson Lee, sent a letter to the president of the Boston Square & Compass Club, Bro. W. L. Terhune, “talking up” the new lodge; he included a detailed (and very positive-sounding) account of the various steps in the history of the movement so far.

At about the same time, Dr. H. C. Mei wrote a letter to the Grand Secretary. In it, he indicated the same level of surprise as the Grand Master at the series of misunderstandings that had taken place thus far. All of the actions that Gillis had found objectionable, including the approach to Bro. Lobingier and the Philippine Grand Lodge, were dismissed due to simple lack of communication; and since patience was being counseled, he consented to wait; but the officers-elect were “now in a quandary from which we should like to be delivered as soon as possible in order that we may take such steps for the future as seem advisable.”

In another letter from Lobingier to Gillis, he as much as accused Gillis of deceiving the petitioners, keeping them waiting for no purpose; in a letter dated January 14, 1929, he hotly rebutted this opinion – but there was no point, he said, in discussing it until the Grand Master’s visit.

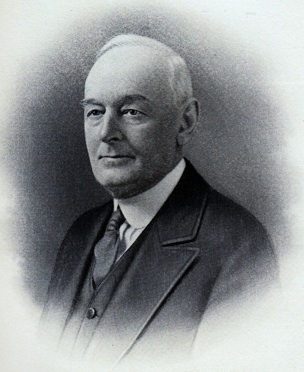

Herbert W. Dean, Grand Master 1929-1931

And while everyone was waiting for the new Grand Master – Herbert W. Dean – to arrive in China, he sent word that theirs would be a long wait. “The first year of a Grand Master’s term of office is perhaps the most important, as in that year such programs as he may wish to inaugurate must be organized and started.” Educational and Service bureaus, the new addition to the Masonic Home, the building of Juniper Hall hospital all made it impossible for him to depart on an extended trip in 1929. “I ask you to continue in the same way for another year, when unless something unforeseen should occur, I will arrange to visit you.”

Grand Master Dean also wrote to Bro. Mei, informing him in no uncertain terms that Rt. Wor. Bro. Irvin Van Gorder Gillis was his personal representative in China and “that all correspondence regarding the proposed Chung Hua Lodge be directly with him or that copies of all letters bearing on the subject should be sent to him.” He sent a similar letter to Bro. Terhune, suggesting that all such appeals should be presented to Gillis and not to him for the time being.

In other words, Gillis would be in the loop – and there would be no more misunderstandings.

“WE HAVE WEATHERED SEVERE STORMS”

With the visit of the Grand Master in abeyance, Gillis’ position as District Grand Master – with the full confidence of his superior behind him – began to take a more assertive tack with respect to inquiries from those who wanted to move ahead with Chung Hua Lodge. In his letter to Grand Master Dean, he was glad to acknowledge his superior’s support in his role as District Grand Master. “Things are not any too happy and smooth with us generally here in China at present, but we have weathered severe storms in the past and we shall probably weather this one.”

He offered a conciliatory but firm tone to the new District Grand Master of the English Constitution, but in correspondence with Wor. Joseph Potter, one of the petitioners for the new lodge, he was far more direct.

In response to Bro. Potter’s question why there was so much controversy over the petition, Gillis noted that “the setting up of this proposed new lodge is actually the first concrete step toward full Masonic independence here in China, with all that that implies.” This was in stark contrast to lodges such as Hykes Memorial, which had not been such a stepping stone.

He was just as forthright in other matters. The YMCA, Gillis charged, had stopped being a “Christian” organization, but had become essentially a political extension of the Kuo Min Tang, and that there were other pernicious movements to divide and conquer foreign elements in China. He asserted

“My actions are governed not only by my desire but my solemnly pledged duty to protect Masonry to the fullest extent within my power, and as a consequence I wil be protecting our sincere and worthy Chinese brothers against their own folly in relying upon the fairness and justice of their own so-called government and officials; as well as of some of their so-called brothers, who belie the designation.”

On May 21, 1929, as if to underscore his position on Chung Hua, he sent the Grand Master a clipping from the North China Standard, describing the concept of “Preaching Hate”. It detailed, in clear and straightforward editorial terms, that hate of things non-Chinese was taught from grade school onward. In another clipping saved in the correspondence archive, it was noted that the Y. M. C. A. – Bro. Adamson’s employer – had come under criticism for becoming politicized. Grand Master Dean sent a short note of appreciation for this correspondence, noting that he had received no more correspondence from Dr. Mei – or anyone else dealing with the proposed lodge.

This correspondence between Gillis, the Grand Master, and various participants went on all summer and fall of 1929.

In October, the new Master-elect of the proposed lodge, Wor. Bro. Joseph Potter, wrote a letter to Gillis to express his thoughts. He noted three principal objections on Gillis’ part to the proposed lodge: first, that there were “political complications”; second, that it might lead to a Chinese grand lodge; and third, that there might be a desire for “purely Chinese Lodges.”

With respect to the first objection, he noted that he had never heard Chinese Brethren speak in the terms Gillis described, and that the majority of the petitioners were, in fact, foreigners. He dismissed the possibility of political consequences as “unlikely.” He further dismissed the idea that the government might have any interest in getting involved.

He was also dismissive of the idea of a Chinese grand lodge. “While it seems to be in the air it has not even been discussed as a practical possibility.” Even if it was being considered, he felt that it could not come to pass for at least five years, and there would still be influential foreigners on site to help prevent it. And what could Chung Hua lodge do, he asked? Nothing.

As for purely Chinese lodges, he noted that the Chinese were not seeking that now, as far as he knew, but in any case, it was not a part of the mission of Chung Hua’s petitioners.

A few weeks later, Bro. Potter sent a circular letter to the members of the proposed lodge. In it, he noted that the process to try and obtain the lodge had already lasted more than a year and a half, and that correspondence with the District Grand Master had been “lengthy and somewhat involved” but that when the Grand Master visited in the Spring of 1930 there would be a definitive answer to their request. His tone was upbeat and optimistic, implying that the answer from Grand Master Dean would be yes. He wrote:

In anticipation of a visit which we rather expected in the spring or early summer of 1929, your officers-elect prepared a pamphlet setting forth the aims and purposes of Chung Hua Lodge. . . It may be that these will be used in the coming spring in the way in which they were originally intended. The proposed lodge had apparently been fairly well capitalized; more than $860 had already been spent on various expenses, with about $400 left in the treasury – very healthy sums in the fall of 1929.

“A VERY LIVELY INTEREST”

In the fall of 1929, the petitioners and the District Grand Lodge were in much the same position as they had been a year earlier: waiting for the visit of the Grand Master of Masons in Massachusetts. The Chung Hua brethren were eager to communicate directly with Grand Master Dean and show him the possibilities for international cooperation in Shanghai and elsewhere in China; District Grand Master Gillis was hopeful that the pragmatic occupant of the Grand East – of whom contemporaries said he was “carved from Berkshire stone” – would see how hollow such a claim might be.

On November 14, Bro. Potter wrote a letter to Bro. Gillis, describing a meeting he had with Bro. Thurston Potter, Past Master of Shanghai Lodge, who had recently returned from Boston, where he had been able to speak directly with the Grand Master. Bro. Dean informed him of his intention to travel to China by way of England and Scotland, and that the Chung Hua matter would be under discussion there.

“From what I gather, he [the Grand Master] expressed a very lively interest in the matter and the serious purpose of settling the question right . . .

“I asked Wor. Bro. Porter whether he [again, the Grand Master] understood thoroughly the circumstances connected with the application made to Massachusetts. It turns out that he really did not understand that the group here might by this time have been operating fully under the Grand Lodge of the Philippine Islands if it had not been directed towards Massachusetts by some of us in Shanghai . . . and following out . . . a policy of spreading Masonry all over the Far East? If this is not well known in Massachusetts, I certainly think it would be the wise thing to make it known there."

We are not in possession of any reply to this letter, but there is a reply to a subsequent one dated February 4, 1930, asking Bro. Gillis if it might be possible for the committee of Chung Hua Lodge to invite the Grand Master to a dinner during his planned visit in June. Gillis replied that he assumed that the Grand Master would be likely to assent to such a meeting. He wrote:

“Let me assure you now and most emphatically: as far as I am personally concerned I shall endeavor to see that nothing shall interfere with your application for a Dispensation being given an unbiased judicial hearing before the Grand Master. You, and the brethren associated with you, know my views, as expressed to you when in Shanghai last October . . . but whatever my views may be, you and your associates are entitled to hold and express yours, and I shall try to see that you are given full opportunity to express them.”

This remarkably even-handed response could be viewed cynically – that the District Grand Master was trying to convey fairness in a matter on which he had especially biased views; but from the distant remove of history, and all evidence of the high regard in which Gillis was held, it is more likely that he was indeed willing to entertain the idea that Grand Master Dean should listen to their presentation and decide for himself. Gillis concludes his letter with the words: “Congratulating you on the spirit of patience you have all exhibited under peculiar circumstances.”

THE DECISION

The 1930 Proceedings give a very full account of Grand Master Dean’s overseas trip. He sailed from Boston on March 20 and spent almost two weeks in England, including a Masonic conference in London with English dignitaries; he visited France, including the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and battlefields of the Great War; and then traveled by train and steamship to Egypt and by ‘aeroplane’ to Karachi and Bombay. While in India he visited the Taj Mahal, then went by train to Calcutta and then Rangoon. By the time he departed by ship to Singapore, he had already been away from Massachusetts for two months.

During the first week of June, the Grand Master arrived in Hong Kong; after a few days he went by train to Shanghai, where he visited all three of the Shanghai lodges under American Constitution and made a fraternal visit to an English lodge. He also met with the petitioners of Chung Hua Lodge on June 10, where he gave them the hearing they had desired for nearly three years.

Afterward he departed for Peking, where he attended the District Grand Lodge of China and International Lodge; he then traveled to Peking, Tientsin and Mukden. In early July he sailed for Honolulu, then spent a few weeks there and in California before finally traveling by train across the country to return to Massachusetts on August 5th – a nearly five month’s circumnavigation of the globe. In the spring and summer of 1930, that would have been an extraordinary trip.

At last, on August 12, 1930, he wrote to Brother Potter and the other petitioners for Chung Hua Lodge, giving them his decision with regard to their request for a dispensation. His answer was in the negative.

He wrote:

“I have given careful consideration to your request for a dispensation to form a new Lodge in Shanghai to be known as Chung Hua Lodge. In considering the question I have endeavored to throughly investigate and study all matters which might assist me in reaching a wise decision . . .

“Your original idea was the formation of an international lodge such as our International Lodge in Peking. This I do not believe is possible owing to local conditions. There is only one lodge in Peking and there are lodges under four constitutions in Shanghai, which would naturally draw to themselves certain candidates tending to make the proposed new Lodge one eventually controlled by the Chinese.

“While there is no doubt in my mind that such a Lodge will eventually be formed, it should only be formed under such conditions as will insure it a future in accordance with the best Masonic traditions. . .

“Our experience during the past few years with new Lodges in the China District has not been encouraging. The Lodges in Canton and Nanking have gone out of existence and I see no future for Talien Lodge in Darien, entirely due to the unsettled conditions. It grows increasingly difficult for the older Lodges to carry on, and it would be doubly hard for a new Lodge. . .

“I am therefore obliged to refuse to grant a dispensation to Chung Hua Lodge, believing that I am acting for your best interests as well as those of Massachusetts Masonry.”

This letter was conveyed to the petitioners, as per his earlier indications, from the Grand Master through District Grand Master Gillis.

AFTERMATH

In some respects, this entire process is no more than a footnote, a failed attempt to create a lodge in a place and at a time where things were unsettled. It would get worse in China – much worse, in fact: within five years there was not only a civil war in being between Nationalist and Communist forces, but an ever-increasing incursion by an aggressive and hostile Japanese military, as well as the difficult economic conditions occasioned by the Great Depression. The lodges under Massachusetts constitution continued to operate; Shanghai inaugurated a new Masonic Temple while Grand Master Dean was visiting, and it was very active.

Irvin Van Gorder Gillis withdrew from the District Grand Mastership in 1936 and was succeeded by Virgil Bradfield, who had been an active officer in the China District for more than ten years. He remained in China, working as an ombudsman for a book collector and importer; he deserves an enormous credit for having arranged for thousands of ancient books of various kinds to be sent abroad – many others of the same kind were destroyed by the Japanese and later by the Communist Chinese when they took power in 1949.

Gillis himself never left China. He was arrested in 1940 when the Japanese took Shanghai, but unlike some of his Masonic colleagues he was not harmed or sent to a prison camp: he had a mild heart attack and was confined to his home, where he remained in virtual house arrest for most of the Second World War. He died in 1948, having seen the ravages of war destroy much of the China he had known and loved. He did not live long enough to see the restored country be changed again by Mao Tse-Tung’s revolution.

The District Grand Lodge of China lost most of its records and much of its membership as a result of the war, but was on the way to recovery when it was again overwhelmed in 1948-1950. While five lodges – Shanghai, Sinim, International, Hykes Memorial and Ancient Landmark – are still listed on the roll of Massachusetts lodges, all but Sinim Lodge have been in permanent recess since 1952. Sinim itself obtained permission to relocate to Tokyo in that year and has prospered in its new home, still under the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts.

The question arises whether this incident has any real meaning in view of the storm that was about to consume the District Grand Lodge. In the grand scheme, the answer is definitely no; the world of the western concessions in Shanghai and elsewhere is long since destroyed. But it does provide a useful insight into that lost time, and the attitudes of the many Brothers who labored in the quarries there – and how they viewed the vast country and people with whom they interacted and from whom they forever felt separate.

LINKS

Grand Master Simpson

Grand Master Dean

District Grand Master Gillis