MAGLJMurray

Contents

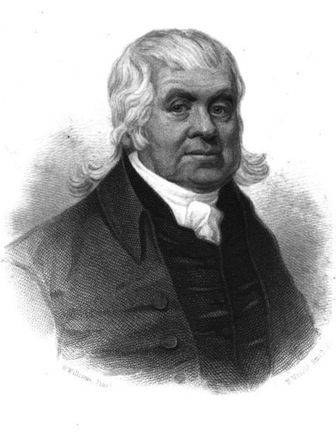

JOHN MURRAY 1741-1815

- MM before 1800, Rising States

- Affiliated by 1805, Columbian

- Grand Chaplain 1803, 1806-1810

BIOGRAPHY

FROM PROCEEDINGS, 1873

From Proceedings, Page 1873-201:

REV. JOHN MURRAY, BOSTON, Universalist. 1805-07, 1809-10.

REV. JOHN MURRAY was the first pastor of the first Universalist Society in Boston, over which he was settled in 1793. He had the reputation of having been the first preacher in America of the doctrines peculiar to his sect. He was born in England, December 10, 1741, and came to this country in 1770. He served as chaplain in the American army, in the war of the Revolution. In the month of May, 1775, the leading officers of the Rhode Island Brigade, assembled in the neighborhood of Boston, despatched a respectable messenger with a letter soliciting the attendance of the Promulgator as chaplain to their detachment of the Revolutionary Army." Severe sickness did not permit him to remain long in the service, but while in it, Gen. Washington honored him "with marked and uniform attention." As a Mason, Brother Murray was devoted and zealous. He officiated one or more terms as Grand Chaplain of the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts. He died in Boston, Sept. 3, 1815. —History of Columbian Lodge, 1856.

The records of Columbian Lodge furnish the following: — "At a special meeting of Columbian Lodge, June 24, 1800, for the purpose of dedicating Masons' Hall (on Ann street), Bro. Murray made a prayer adapted to the subject, and Rev. Bro. Harris delivered an address on the occasion.

— See History of C. L.

The biographies by Allen and Drake are referred to for further information. "Mr. John Murray, a native of England, who arrived in America before the commencement of the Revolutionary War, had preached in New Jersey, in Philadelphia and New York, some time previous to his coming into New England. . . The life of Mr. Murray having been published since his death, and circulated considerably among our societies, it will be the less necessary to enter very minutely into his history. We shall do no more, in this place, than merely sketch A brief outline of his character as an early laborer in the vineyard of the Lord, and a firm and undaunted soldier, enduring hardness in the cause of the Captain of our salvation.

In point of doctrine, Mr. Murray was really and professedly a disciple of Mr. Kelley, whose peculiar views of the Gospel need not be detailed here, as they were explained at large in the department of this work to which they properly belong. In the manner of his preaching, Mr. Murray was always greatly interesting and could command the most profound attention in the greatest audiences. It has been often said that Mr. Whitefield was his model, and it is not unlikely that, from his intercourse with that gentleman in early life, having been a member of his communion, and from the regard and reverence he bore to him, he might, without intention, have copied his manner in proportion as he imbibed his spirit. He was powerful, yet cold and dispassionate in argument. He possessed a vast acquaintance with the Scriptures; and few men could apply with so much ease and readiness their figurative expressions, to illustrate the great doctrine of the Gospel. To a fervid imagination and a vigorous intellect, he had in addition a strong and retentive memory, which had ever been much exercised. He had read many theological works, the principal features of which he always distinctly recollected; and he could, frequently, when quoting an author in public, give his ideas in his own words. It has been sometimes urged against Mr. Murray that he indulged too much in a spirit of sarcasm and satiric wit. That he possessed these powers is well known, and that, at certain times, he employed them is not denied.

We believe, however, that in the later periods of his life he sincerely regretted his use of those powers in his public character. To the writer of this article he once said, "If you possess wit, if you have a talent for satire, never cultivate, never indulge in them. They will not produce you any sincere friends; they will make you many enemies. It is no way to catch birds, by casting stones at them." Mr. Murray was a chaplain in the American Army during a great part of the Revolution, and for a considerable time attached to the family of Gen. Washington,

His first establishment in the ministry was at Gloucester, on Cape Ann; the next and last, at Boston, where a large and respectable society had been gathered by his instrumentality. He continued to labor with them in word and doctrine constantly, with the exception of visiting, once in a few years, Philadelphia, Baltimore, New York, etc., in which places he had numerous friends, until the autumn of 1809, when he was seized with a paralysis which interrupted his regular labors; and except in a few instances, when he was carried into the pulpit, he never preached more. Still his mental powers were not so much impaired as we should have expected from his age and the nature of his disease; and in his protracted hours of pain and languor, we have often been struck with admiration at that force of genius and activity of mind which he continued to exhibit. The faith which he had so long preached to others was his spiritual support under all his infirmities; and on the 3d of September, 1815, he quietly departed this life, in the "hope, full of immortality." Thus died one who, when our country was morally a wilderness, "went forth weeping, yet bearing precious seed," and lived to see that seed spring up and flourish, and to " return again rejoicing, and bringing his sheaves with him."

— Note on pp. 167, 168 Universalist Quarterly, 1871.

FROM NEW ENGLAND CRAFTSMAN, 1916

From New England Craftsman, Vol. XII, No. 2, November 1916, Page 52:

Rev. John Murray

Chaplain of the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts 1805-1807, 1809, 1810.

Among the Reverend brethren who have served the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts as chaplains the name of John Murray stands among the foremost to attract our attention.

John Murray was born December 10, 1741, in the town of Alton, Hampshire, England. His father was an Episcopalian, his Mother a Presbyterian. His parents were very religious and the boy was brought up under the most strict rules of conduct.

In the opinion of his father pleasure of life and sin were synonymous. The boy was remarkable for his intelligence which according to the following story was manifested at a very early age. The incident as related by himself is as follows:

"My mother believed, as most good women then believed, that husbands ought to have the direction, especially in concerns of such vast importance, as to involve the future wel1 being of their children, and of course it was agreed, that I should receive from the hands of an Episcopalian Minister, the rite of private baptism; and as this ordinance, in this private manner, is not administered, except the infant is supposed in danger of going out of the world in an unregenerate state, before it can be brought to the church. I take for granted I was, bv my apprehensive parents, believed in imminent danger; yet through succeeding years, I seemed almost exempt from the casualities of childhood. I am told that my parents, and grandparents, had much joy in me, that I never broke their rest nor disturbed their repose not even in weaning, that I was a healthy, good humored child, of ruddy complexion, and that the equality of my disposition became proverbial. I found the use of my feet before I had completed my first year, but the gift of utterance was still postponed. I was hardly two years old, when I had a sister born; this sister was presented at the baptismal font, and, according to the custom in our Church, I was carried to be received, that is, all who are privately baptized, must, if they live, be publicly received in the congregation. The priest took me in his arms, and having prayed, according to the form made use of on such occasions, I articulated, with an audible voice, Amen. The congregation were astonished, and I have frequently heard niy parents say this was the first word I ever uttered, and that a long time elapsed before I could distinctly articulate any other."

It is almost painful to read the story of the discipline of young Murray during his childhood. It was enough to crush all the brightness and cheerfulness out of life. The routine of a day is given by him as follows:

"It was my father's constant practice, so long as his health would permit, to quit his bed, winter as well as summer, at four o'clock in the morn-ing; a large portion of this time, thus redeemed from sleep, was devoted to private prayers, and meditations. At 6 o'clock the family were summoned, and I, as the eldest son, was ordered into my closet, for the purpose of private devotion. My father, however, did not go with me, and I did not always pray; I was not always in a praying frame; but the deceit, which I was thus reduced to the necessity of practising, was an additional torture to my laboring mind. After the family were collected, it was my part to read a chapter in the Bible; then followed a long and fervent prayer by my father; breakfast succeeded, when the children being sent to school, the business of the day commenced.

In the course of the day, my father, as I believe, never omitted his private devotions, and, in the evening, the whole family were again collected, the children examined, our faults recorded, and I, as an example to the rest, especially chastised. My father rarely passed by an offence, without marking it by such punishment as his sense of duty awarded; and when my tearful mother interceded for me, he would respond to her entreaties in the language of Solomon, 'If thou beat him with a rod, he shall not die;' the Bible was again introduced, and the day closed by prayer. Sunday was a day much to be dreaded in our family; we were all awakened at early dawn, private devotions attended, breakfast hastily dismissed, shutters closed, no light but from the back part of the house, no noise could bring any part of the family to the window, not a syllable was uttered upon secular affairs; every one who could read, children and domestics, had their allotted chapters. Family prayer succeeded, after which, Baxter's Saint's Everlasting Rest was assigned to me, my mother all the time in terror lest the children should be an interruption. At last the bell summoned us to Church, whither in solemn order we proceeded; I close to my father who admonished me to look straight forward, and not let m eyes wander after vanity. At church, I was fixed at his elbow, compelled to kneel when he kneeled, stand when he stood, to find the Psalm, Epistle, Gospel and collects for the day, and any instance of inattention was vigilantly marked, and unrelentingly punished. When I returned from church, I was ordered to my closet; and when I came forth, the chapter, from which the preacher had taken his text, was read, and I was then questioned respecting the sermon, a part of which I could generally repeat. Dinner, as breakfast, was taken in silent haste, after which we were not suffered to walk, even in the garden, but every one must either read, or hear reading, until the bell gave the signal for afternoon service, from which we returned to private devotion, to reading, to catechising, to examination, and long family prayer, which closed the most laborious day of the week."

When John Murray was about eleven years old his family removed to Ireland. Here he came under the influence of the Methodists. With this religion he was "greatly enamoured." The singing at the service and the gathering of the young people was much more cheerful than what he had experienced before. In the course of his twelfth year his father was overtaken with a heavy calamity; his house and almost everything he possessed were laid in ashes.

Assistance was provided by the paternal grandmother of John to whom he became much attached; devoting a large part of his time to her company. This pleasant experience lasted but a short time as his father found it necessary to remove to another town where John immediately attracted the attention of the resident clergyman who desired to take him into his home to be prepared for college after which he proposed to send him to Trinity College, Dublin. His father refused consent, fearing it would endanger his "spiritual interest." This was the second instance where the conscience of the father deprived the son of opportunity that would have advanced his material prosperity. The first was a chance inherit property of a deceased grandfather in France. This depended recanting of the English Church, his grandmother which by the advice of his father she refused to do. As John advanced in years he commended the action of his father in this business.

We are not informed of the nature of the business in which young Murray entered. It was something under the eye of his father who was determined that he should not be exposed to the temptation of the world.

The record of Murray's life for several years is a monotonous account of praying and preaching which he began informally at an early age. There were times when his nature revolted from a religious life so strenuous and he found relaxation in the society of his friends.

While Murray was a young man his father died and he determined to start out in the world on his own account. He determined to go to England. He was opposed strongly by his mother and others, especially by a family who had shown him great affection and with whom he was urged to make his home and fill the place of a deceased son. This benefactor furnished him with a liberal sum of money on their parting. His trip to London was interrupted by delays in Bristol and Bath where he spent some time with congenial religious acquaintances. Arriving in London he came under the influence of another sort and it was not long before he gave himself up to a new life. He says:

"Every day I was more and more distinguished; but it was by those, whose neglect of me would have been a mercy; by the nominal kindness I was made to taste of pleasures, to which I had before been a stranger, and those pleasures were eagerly zested. I became what is called very good company, and resolved to see, and become acquainted with life; yet I determined my knowledge of the town, and its pleasures, should not affect my standing in the religious world.

"But I was miserably deceived; gradually, my former habits seemed to fade from my recollection. To my new connections I gave, and received from them, what I then believed pleasure, without alloy. Of music and dancing, I was very fond, and I delighted in convivial parties; Vaux-hall, the playhouses, were charming; I had never known life before. It is true, my secret Mentor sometimes embittered my enjoyments; the precepts, the example of my father stared me in the face; the secret sigh of my bosom arose, as I mournfully reflected on what I had lost. But I had not sufficient resolution to retrace my steps; indeed I had little leisure. I was in a perpetual round of company; I was intoxicated with pleasure; I was invited into one society, and another, until there was hardly a society in London, of which I was not a member. How long this life of dissipation would have lasted, had not my resources failed, I know not."

This life continued until his money was all expended when he awakened to a sense of his condition. He dropped his wordly associates, secured employment, gradually paid his debts and returned to the society of religious people and the duties of a religious life. This change brought him acquaintance with a beautiful lady, the sister of a church friend, to whom he was married after several months' delay and the strenuous opposition of the young woman's grandfather with whom she lived. The grandfather exhibited his displeasure by bestowing on another the fortune he had intended for her.

The marriage was the union of two congenial souls but was not destined to last long. A child was born only to survive a year. Soon after this the wife was removed and Murray was left alone burdened with debts and forsaken by friends for soon after his marriage he and his wife had Income interested in the religious teachings of Relly, a liberal preacher, who advocated the doctrines of the Universalist. To follow Relly was to cut themselves off from the friendship of all their church associates.

The prolonged sickness of Murray's wife occasioned expense and debts that he was unable to meet. The forbearance of his creditors became exhausted and at last he was taken by writ and "borne to a spunging-house." He was so much discouraged that he found, in the expected seclusion "a kind of melancholy pleasure." He refused sustenance and would have no bed as a "bed must be paid for" and he was penniless. He slept on the floor of a room hung with cob-webs. He relates his experience as follows:

"The barred windows admitted just enough light to announce the return of day; soon after which, the keeper unlocked the door, and in a surly manner, asked me how I did? Indifferent, sir, I replied. 'By G—, I think so! but, sir, give me leave to tell you, I am not indifferent, and if you do not very soon settle with your creditors, I shall take the liberty to lodge you in Newgate. I keep nobody in my house that does not spend anything, damn-me. I cannot keep house, and pay rent, and taxes for nothing. When a gentleman behaves civil, I behave civil; but, damn-me, if they are sulky, why then, do ye see, I can be sulky too; so sir, you had better tell me what you intend to do?' Nothing. 'Nothing? Damn-me, that's a good one; then, by G—, you shall soon see I will do something, that you will not very well like.' He then turned upon his heel, drew the door with a vengeance, and double-locked it. Soon after this, his helpmate presented herself, and began to apologize for her husband; said he was very quick; hoped I would not be offended, for he was a very good man in the main; that she believed there never was a gentleman in that house (and she would be bold to say, there had been good gentlemen there, as in any house in London) who had ever any reason to complain of his conduct. He would wait upon any of my friends, to whom 1 should think fit to send him, and do all in his power to make matters easy; 'And if you please, sir, you are welcome to come down into the parlor and breakfast with me.' And pray, my good lady, where are you to get your pay? 'O, I will trust to that, sir; I am sure you are a gentleman; do sir, come down and breakfast; you will be better after breakfast. Bless your soul, sir, why there have been hundreds, who settled their affairs, and did very well afterwards.' I was prevailed upon to go down to breakfast. There was, in the centre of the entry, a door half way up, with long spikes; every window was barred with iron; escape was impossible; and indeed I had no wish to escape; a kind of mournful insensibility pervaded my soul, for which I was not then disposed to account, but which I have since regarded as an instance of divine goodness, calculated to preserve my little remains of health, as well as that reason, which had frequently tottered in its seat. To the impertinent prattle of the female turnkey I paid no attention, but hastily swallowing a cup of tea, I retired to my prison. This irritated her; she expected I would have tarried below, and as is the custom, summoned my friends, who, whether they did anything for my advantage or not, would by calling for punch, wine, etc., unquestionably contribute to the advantage of the house. But as I made no proposal of the kind, nor indeed ever intended so to do, they saw it was improbable they should reap any benefit by or from me; and having given me a plentiful share of abuse, and appearing much provoked, that they could not move me to anger, they were preparing to carry me to Newgate, there to leave me among other poor, desperate debtors; and their determination being thus fixed, I was at liberty to continue in my gloomy apartment; and, what I esteemed an especial favor, to remain there uninterrupted. I received no invitation either to dinner, tea, or supper; they just condescended to inform me, when they came to lock me in, that 1 should have another lodging the ensuing night; to which I made I no reply. My spirits, however, sunk in the prospect of Newgate. There, I was well informed, I could not alone; there I knew, my associates would many of them be atrocious offenders, and I was in truth immeasurably distressed."

He was relieved from his embarrassing situation by his deceased wife's brother and established in business by means of which he finally was freed from debt.

The death of his wife appears have preyed on the mind of Murray and prevented him from finding comfort in any occupation or society. He was sick of the world and hoped for death. At this time he met a gentleman from America. He became interested in the description of the country and its people and of the peace and plenty which they enjoyed. He determined to go to America. His mother and other relatives tried to change his mind but without avail. He engaged passage on a Brig, the Hand in Hand, sailing for New York. He went on board the vessel July 21, 1770, on the following morning she sailed. When within about three days' sail of New York, they met a vessel bound for England, the captain of which was questioned respecting the state of public affairs in America. The Americans had some time before entered into a non-importation agreement. The owner of the merchandise on the Hand in Hand appears to have been on board. He was anxious regarding the delivery of his property and when he was informed that the merchants of Philadelphia had given up the non-importing agreement he directed the captain to proceed to that port.

When they were near enough to take on a pilot, he informed them that the reverse of their first information was true. To make sure in the matter their course was continued to Philadelphia. It was in the month of September when they arrived in Delaware. Murray was enchanted with the country as he was surprised at the magnitude of Philadelphia when he reached it, as he had supposed the country to be a wilderness.

The vessel resumed her trip for New York but struck on a bar in a fog which made it necessary to lighten the vessel; this was done by transferring a portion of the cargo to a sloop on which Murray went in charge of the goods. Contrary winds prevented the sailing of the vessel. There was no supply of food on the sloop and Murray went on shore in search of something to eat. This circumstance led him into a path of influences that compelled him to become a preacher, a profession that he reluctantly accepted but which he successfully followed until the end of his life.

Without attempting to follow John Murray in his various experiences before he became chaplain of the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts, we must briefly tell of his first church settlement. While he was searching for food for the sloop he came to a house where there was a large supply of fish. The owner refused to sell any but willingly gave him all he wanted but what amazed him more was the remark of the man who invited him io stay at his house, saying, "I have longed to see you. I have been expecting you a long time."

Murray was astonished that the man should look upon him as a preacher. It appears that this man, named Potter, had long before become interested in religion, and, having the means to do so, had built a meetinghouse for worship. He had not found any one to officiate as a permanent Minister. Tt is somewhat remarkable that the moment he saw John Murray he was satisfied the right man had come. After considerable reflection Brother Murray decided to remain insisting that he should preach without salary and work on the farm in return for his board. His reputation as a preacher rapidly spread and he was obliged to respond to calls to preach in many places, notably in New York City and Philadelphia.

His teachings were not acceptable to the regular clergy and many of them used their influence to injure the young preacher. In the autumn of 1772 he made his first visit to New England. He preached in Newport where he drew large audiences by the novelty and reasonableness of the doctrine he advocated. He made enemies of many of the clergy.

Following this visit he returned to Philadelphia preaching there and in many other places coming again to Newport, Providence and other New England towns. On the 26th of October, 1773, he took seat in a stage for Boston, where he arrived late in the day.

On the evening of October 30, 1773, he preached his first sermon in Boston in the hall of a factory. From Boston he went to Newburyport, then to Portsmouth, and returned again to Boston where he preached in Faneuil Hall. He was urged to remain in Boston, but felt called upon to return to his patron Potter, preaching at many places on his way. In September, 1774, he was again in Boston. In 1775 he was invited to become a chaplain in the Revolutionary Army. George Washington honored him with marked and uniform attention. After retiring from the Army he was chosen as pastor of a new society in Gloucester. His presence in that town was strenuously opposed by the members of the regular church and he was summoned before a committee of safety who expressed their desire for him to leave the town. He preached his first sermon in a small church that was erected for him in Gloucester, on Christmas Day, of 1780. Mr. Murray not being ordained by the regular ministers was looked upon as an intruder upon their riehts and to the great astonishment of the new church their goods were seized by an officer and sold at auction. The church commenced action for infringement of rights. It was not until June, 1786, that a conclusive verdict in their favor was obtained.

In 1788 Brother Murray embarked for England. Arriving at London he found his venerable parent in the enjoyment of a fine green old age. He preached at many places in England. On his return to America he was in the society of Ex-President John Adams and lady. On Wednesday, October 23, 1793, John Murray was installed in the Universal Meetinghouse in Boston on North Bennet Street. It is said that "Perhaps no congregation were ever more unanimous and more perfectly satisfied with their pastor of their election, than were the people" of this society, and "perhaps no minister was ever more unfeignedly attached to the people of his charge than was the long-wandering preacher."

We have few particulars regarding the connection of Brother Murray with the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts as chaplain. He was first appointed by Grand Master Isaiah Thomas in 1805 with four others from Massachusetts Districts and two for the Maine district, John Murray being the first named in the list. He was again appointed by Grand Master Thomas in 1806, 1809, 1810 and by Grand Master Timothy Bigelow in 1807.

We are unable to state where John Murray received the Masonic degrees Past Grand Master John T. Heard says of him that as a Mason he "was devoted and zealous."

The records of Columbian Lodge record that he was present and made a prayer at the dedication of Masonic Hall on Ann St., now North Street, June 24, 1800.

In 1809 he was seized with a paralysis which interrupted his regular labor, but his life was prolonged until September 3, 1815, when he quietly passed away.